A glimpse of the debate on whether medical tests can prove child abuse

The fate of whether a parent regains custody of their child or spends time behind bars is often left to a judge's perception of credibility.

The accusations made by a child abuse pediatrician, or CAP, are at the heart of the decision to remove a child from their parents, but understanding their job and the process used to make a diagnosis is hard to come by.

Requests for an interview were sent to Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta and the American Academy of Pediatrics - both declined. 11Alive investigates also reached out to the Helfer Society - no response. Very few of the doctors willing to push back against their diagnosis of abuse would sit down for an interview either. Several said they were afraid their words would be used against them in court.

So 11Alive Investigates went to court - where medical professionals couldn't dodge our cameras.

In April, the cameras were rolling at a hearing for an extraordinary motion for a new trial, the legal term given to the type of appeal made by the person accused.

The defendant, Danyel Smith, has spent more than 20 years in prison for killing his baby boy, Chandler, although he insists his son died from a brain injury at birth.

RELATED: Medical experts say science raises question on whether a Georgia father really killed his baby

There are a few injuries that come up the most in these kinds of cases, like retinal hemorrhages, bone fractures, metaphyseal lesions, and subdural hematomas. It’s not important to know what those terms mean; only that two doctors can look at the same X-rays, lab tests, and body scans and come up with very different conclusions about how they happened.

Abuse to one doctor may be rickets, a blood or genetic disorder to another.

In the case of Chandler, child abuse pediatrician Suzanne Starling testified the baby died of abusive head trauma. Dr. Saadi Ghatan, a Mount Sinai pediatric neurosurgeon, testified he died of anoxic brain injury caused at birth.

For judges and jurors, this means a decision on whether a parent goes to prison or loses custody of their child often comes down to credibility.

Approaching child abuse diagnosis

“I’ve been in the field for a long time. How many people do I know, who know what I know? A hundred. Not one is willing to do this. Not one. They said it has nothing to do with money. It’s too frustrating,” said Dr. Michael Laposata, the only medical professional who agreed to be interviewed on the record for this story.

Laposata is the director of pathology at the University of Texas Medical Branch, specializing in blood disorders.

“Some people say we did clotting tests. The trouble is, there’s more than 100 different bleeding disorders named. And so what they do, is they rule out a limited number, five, six and say 'That’s it. We did all the tests,'” he explained. “Sometimes the kid has a rare cause for a bleeding disorder, and you really need an expert.”

Laposata said in 1998, he saw firsthand how a misdiagnosis could put a parent in prison. He’s been analyzing cases free of charge and fighting for parents he feels are innocent ever since.

“Nineteen out of 20 kids with bruises were actually beaten. So the challenge is to find a 1 in 20,” he said. "There’s no requirement for getting an expert like me who signed out 50,000 bleeding and clotting patients to say, 'Is there any underlying disease?' And then, even if there is, there’s no requirement to believe me."

A different approach

Laposata said the key is culture. It's not enough to get a consult from a medical specialist who may feel inclined to assume you're original diagnosis is accurate. Instead, he's created a team of doctors who know their role is to ask questions and challenge his diagnosis if warranted.

Starling, who testified at Smith's hearing in Gwinnett County, said that CAPs are trained to do the same thing: consult with other medical professionals to consider all options.

“About 40% to 50% of the time we actually evaluate children that someone else has thought was abuse, and we don't think it's abuse. And so we go in quite a bit to reverse the decision that another medical provider with less experience has made,” Starling explained.

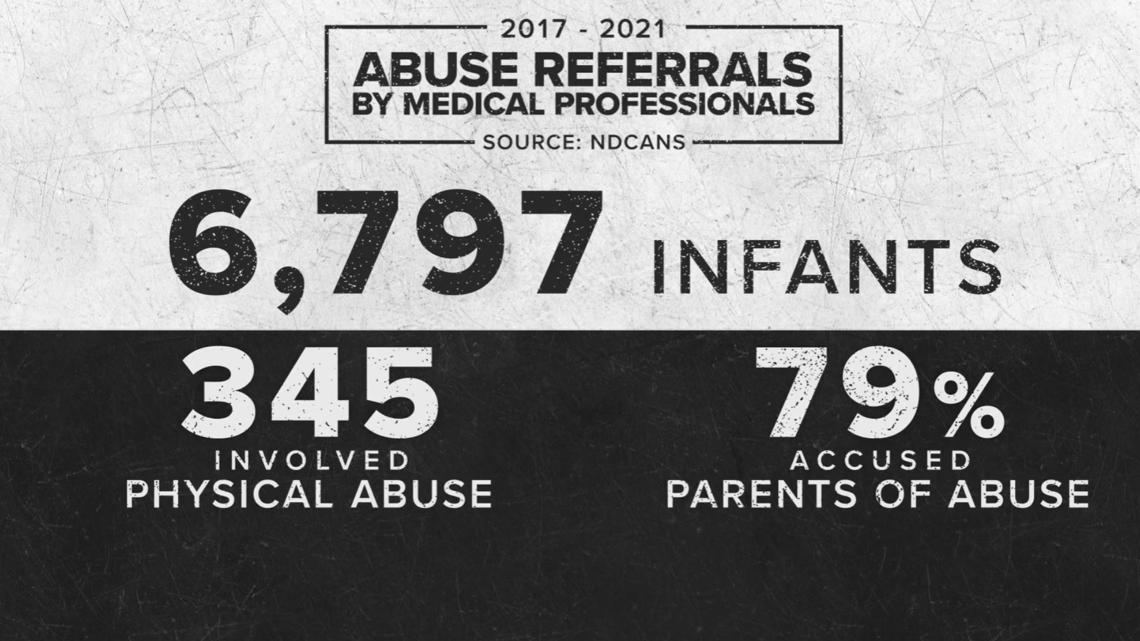

According to the National Database of Child Abuse and Neglect, in a five-year span between 2017 and 2021, medical professionals across the state of Georgia contacted child welfare 6,797 times for some type of suspected abuse involving an infant. Most of those cases were for neglect or some kind of sexual assault. Only 345, or 5% of those cases, were accusations of physical abuse. When a case was substantiated, child welfare usually pointed the finger at the parents.

At another court hearing involving one of the families featured in Help that Harms, Children's Healthcare of Atlanta child abuse pediatrician Stephen Messner put the number higher. He said the team at Children’s consulted on more than 2,000 cases last year and ruled 10 percent to be non-accidental trauma, or abuse.

Children's Healthcare of Atlanta corroborated Messner's numbers in June outlining that within a two-year period, 2022 and 2023, the hospital reviewed 2,216 cases and diagnosed 223 of them as non-accidental. That's about 10% of cases.

11Alive Investigates could not find data on how many of those parents were later found innocent and reunited.

Different interpretations

During Smith’s hearing, attorneys shared images of eyes, brains, and bones. Each expert who testified tried to prove what an injury can—and cannot—say about its cause.

It wasn’t just doctors.

Smith’s defense team brought in a biomechanical engineer to discuss studies around the force necessary to cause various types of injuries to an infant. They also brought in forensic psychologist Jeff Kukucka to talk about the power of cognitive bias.

“It can become problematic in situations where the goal is to establish the objective truth because, by definition, if two individuals look at the same information and come away with two different interpretations, one of them must be factually incorrect,” Kukucka told the judge.

Kukucka studies the role of bias and how to prevent it. He testified a diagnosis by a child abuse pediatrician is different than most.

“We rarely ever find out whether the child actually was abused or not. In contrast, your typical medical diagnosis involves a course of treatment, and the doctor can learn, based on the success or lack thereof, of the course of treatment, something about whether their diagnosis was correct,” Kukucka said. “An expert could consistently diagnose a condition such as abusive head trauma, but there's no way to know whether those consistencies are accurate.”

According to the National Registry of Exonerations, about three dozen people have had their convictions for child abuse-related offenses overturned as the science around these injuries has changed.

It’s why Ghatan said doctors should alert child welfare to protect the baby but gather more information before declaring the injuries abuse.

“We're very careful also not to put a supposition of non-accidental trauma into the medical record immediately, which then taints the view of every practitioner that comes down the line in this era of cutting and pasting medical record,” Ghatan told the judge. “The minute that you posit in the chart that this is not accidental trauma then everybody believes it, and everybody does their best to get out of it as quickly as possible.”

In his testimony, Ghatan was referring to the involvement of a specialist that could either push back against the allegation of abuse or merely rubber stamp the diagnosis and move on.

He has encouraged specialists to speak up when consulted on a case labeled abuse if they feel there could be another reason for the injury, as seen in the 2020 paper "Unlikely to be Abuse: Lean In, Pediatric Neurosurgeon!”

In the article summary, Ghatan writes, “In the setting of self-limited neurological diagnoses such as linear skull fractures and benign extra-axial fluid collections, a pro-active collaboration between pediatric neurosurgeons, child abuse pediatricians, pediatric emergency room staff, and family defense attorneys can help restore order in the court.”

In court, Ghatan put it even simpler.

“When there's an accusation of child abuse, get involved, because if you walk away, that's when people get hurt," he said.

The judge has yet to decide whether to grant Smith a new trial.

11Alive Investigator Rebecca Lindstrom has been looking into the Help That Harms. Follow her investigation on demand via our streaming app 11Alive+ Available on Roku, Apple TV and Amazon Fire TV.