NOTE: The Atlanta Track Club is releasing a series of stories celebrating the upcoming 50th running of the AJC Peachtree Road Race, of which 11Alive is the official broadcast partner. These 50 stories spanning 50 weeks will celebrate a different aspect of the race’s history and legacy.

Clyde Partin Jr. was just 14 years old, and can’t remember why he and his father stopped by the cinder track at Emory University that day in June 1970. It probably wasn’t for anything important. But he does remember that when they arrived, he and Clyde Sr. were approached by Tim Singleton, who invited them to “a little race down Peachtree” on July 4.

As the AJC Peachtree Road Race kicks off a yearlong celebration of its 50th running on July 4, 2019, Partin – who along with his father is one of the “Original 110” finishers – is already looking forward to “the great moment.”

He is not alone: the AJC Peachtree Road Race – despite being run in the heat and humidity of summer in the South on a course whose most-famous feature is the ominously nicknamed Cardiac Hill – has grown to 60,000 participants, making it the largest road race in the United States and the largest 10K in the world.

“Even if people should’ve found something better to do with their Fourth of July mornings, they don’t seem to do it,” said Steve Hummer, who began writing for the Atlanta Journal Constitution in 1989. “It has become essential to observing the Fourth of July in Atlanta.”

As the milestone approaches, it’s a good time to pause and ask: What is it about “the Peachtree” that prompted then-Mayor Shirley Franklin to once call it the one thing Atlanta wouldn’t be the same without?

The race’s success involved good timing: It was born on the cusp of the 1970’s running boom, fueled by Frank Shorter’s 1972 Olympic gold medal in the marathon. It involved a little savvy: the AJC came on as sponsor in 1976, providing publicity and promotion at exactly the moment needed for the race to take root. And it involved a little luck: Winning the first race was Jeff Galloway, a man who would later help bring in friends like Shorter, Bill Rodgers, Don Kardong and four-time Olympic gold medalist Lasse Viren to compete.

But it’s likely that the Peachtree became what it is today through something less tangible: The race and the city are, at heart, one and the same.

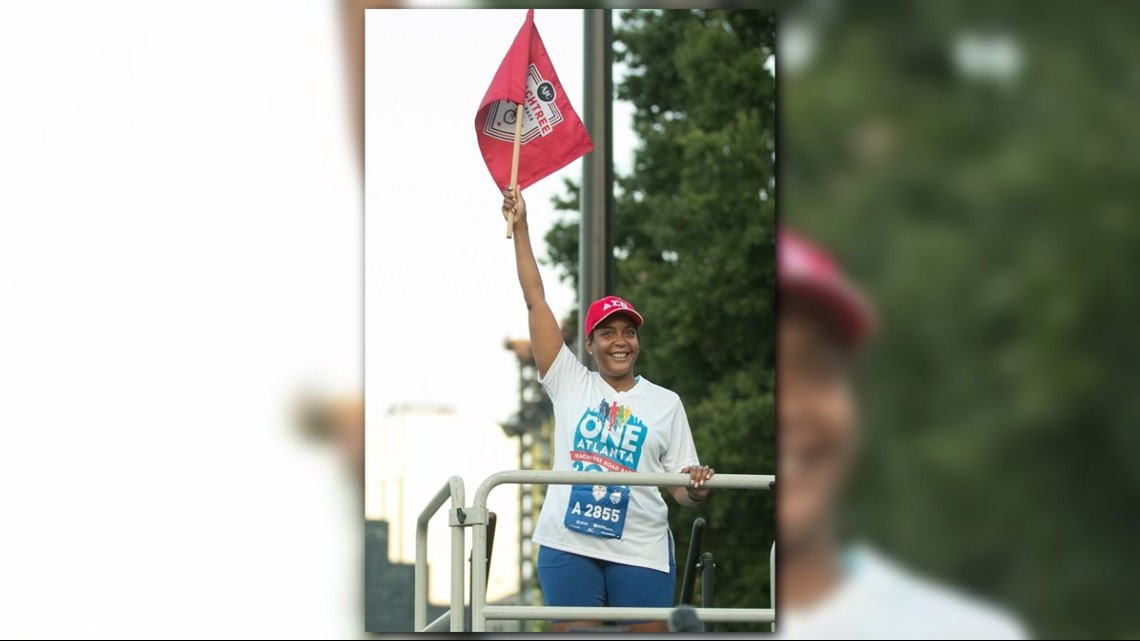

Said Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms after finishing this year’s race: “What makes the Peachtree special is, it’s Atlanta.”

“It’s the people,” agreed Galloway, who after winning the inaugural Peachtree went on to become a 1972 Olympian and author. “Atlanta has a long tradition of people wanting to work together for the common good and people wanting to come together with energy to make something good happen.”

“People want to work,” said Galloway, who has lived in Atlanta since he was 13. “They want to help you.”

The degree to which that’s true surprised even Rich Kenah when he moved to Atlanta from the Northeast to become executive director of Atlanta Track Club and race director of the Peachtree in 2014. No stranger to the fraught negotiations it sometimes takes with city officials to produce an event, Kenah found that negotiations on the Peachtree were so smooth that they could hardly be called negotiations.

“The Atlanta chief of police and his department, the city, (then-)Mayor Reed, the CEO of MARTA … without exception they all asked me what they could do to help continue the tradition of the race,” he recalled. “It struck me that they were communicating to me a genuine understanding that this event is our collective responsibility.”

The 2014 Peachtree was Kenah’s first, and he said it wasn’t until he stood watching the last person come across the finish line “that I began to understand what the event is and what it means for the city.”

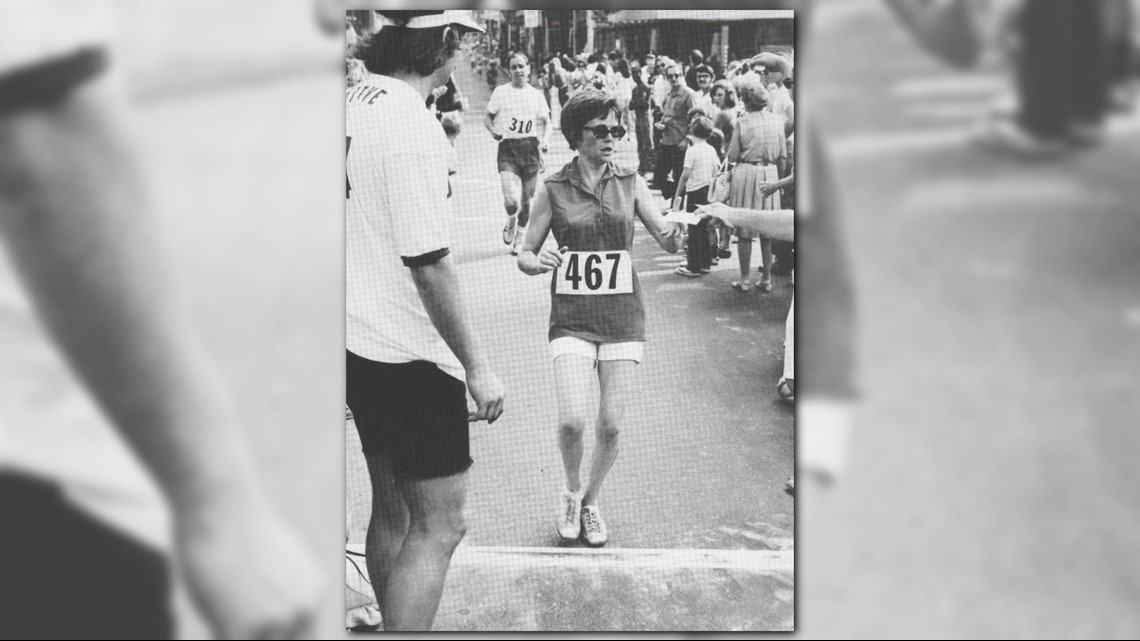

A lot of that meaning can be traced back to Julia Emmons, who led Atlanta Track Club and the Peachtree for 22 years, from 1985 to 2006. From the first day of her tenure, Emmons decided her job was to pay attention to serving the community. She delegated total responsibility for the field of elite athletes – which routinely featured many of the best from across the globe – and focused entirely on the pack.

Or, rather, on a pair of representative runners she thought of as Dorothy and Frank.

“You can’t imagine 25,000 people, but you can imagine two people times 12,000,” she said. “If we change the water stops, how does that affect Dorothy and Frank? This is very real. Running Peachtree to them is a big deal.”

Former mayor Shirley Franklin wasn’t the prototype for Dorothy, but she might have been. “When I ran the race, I was just glad I could get from beginning to end,” she said. “I think there are a healthy percentage of people out there just like me.”

In her first year at the helm, Emmons was asked afterward if she realized there had been crying children in the race. She ran every year thereafter, tending on foot to her flock.

“I care about each and every person in the race,” she said. “And if the children were crying, I wanted to know why.” Her findings helped lead to establishment of Peachtree Junior, a separate event for younger children.

But when changes were needed, she realized, they needed to come in on little cat feet rather than those of a Tyrannosaurus Rex. She likened the Peachtree to a favorite summer lake: You don’t want it to look different on the surface, but for it to remain healthy and not grow stagnant it needs to be continually refreshing itself underwater.

It has to feel the same, she explained, even as it changes.

Although there have been tweaks to the start and finish, the run down Peachtree Street –the artery supplying lifeblood to both the city and the race – endures. Sam Massell, who was mayor of Atlanta when the race was founded in 1970 and served as the official starter in 1973, lives on Peachtree, so the event runs right by his house. He said he’s out there almost every year to cheer them on.

Now president of the Buckhead Coalition, Massell is in the perfect position to hear gripes about closing the key street to traffic. Except, there aren’t any.

“Here you have something that gigantic, the largest race known to man, and we don’t get any complaints,” he mused.

If the Peachtree reflects the city in its friendliness, energy and “can-do” attitude, it does so even more with its spirit of inclusion. It may be won by an Olympic medalist or world champion, and often is, but the real race does not belong to the swift.

For one morning, cracked the AJC’s Hummer, “a community made up of transients come together as Atlantans for a few hours to sweat.”

Franklin, the former mayor, took a more serious view. “It’s on our main street and very few things happen on that street that are as joyous or inclusive,” she said. “Nobody worries about who you are or where you came from or how you got there.”

Or, as the two-word slogan on the current mayor’s 2018 race T-shirt proclaimed: One Atlanta. “Running down Peachtree and to have the world’s largest 10K, 60,000 people out here … nothing says Atlanta more. And then to have the diversity, I would be surprised if you find that anywhere else in America.”

The city has gone through several periods of rebirth in its history, perhaps most recently as host city of the 1996 Olympics – around the time, said Kenah, he believes the Peachtree found its place.

“We know what the event is now much as Atlanta knows what it is as a city – a warm and in many ways welcoming place that has a small, hometown feel to it despite its size. At Peachtree, with 60,000 people, you know the name of the person who’s in charge of your wave,” he said. “It’s a place where, if for no other time, from 7 a.m. until 10:50 a.m. we’re all part of one race.”