The untold stories of SunTrust Park: The people most affected by the Braves move to Cobb County

<p><span style="font-size: 12px;">These are the stories that have not been told until now</span></p>

It was a cool, crisp fall morning in Atlanta.

Baseball season had concluded just 12 days prior with the Boston Red Sox winning the World Series.

The Atlanta Braves had come up short in the postseason, losing to the Los Angeles Dodgers in four games in the NLDS. The long offseason had just begun, and the Braves weren't at the forefront of anyone's mind when Nov. 11, 2013 began. By afternoon, the Braves were one of the biggest stories nationwide.

A video emerged:

"Today, I would like to announce that the Atlanta Braves would like to build a new ballpark, which will open in time for the 2017 baseball season. The new location is a short distance from Downtown Atlanta, at the intersection of I-75 and I-285," then-Team President and Hall of Famer John Schuerholzer said.

You know the rest.

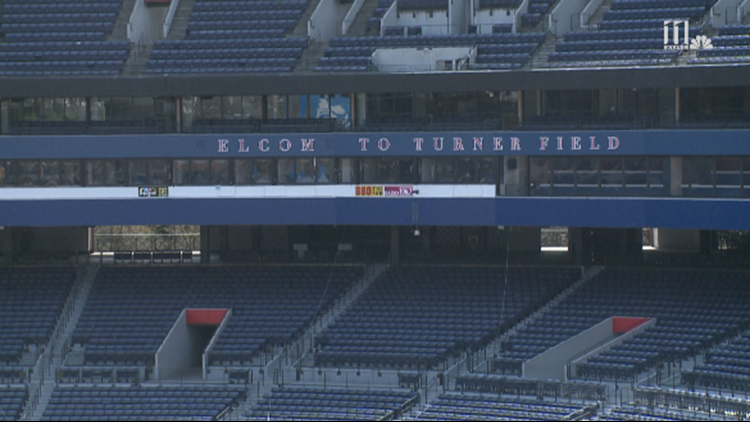

First came the initial shock. The Braves said hundreds of millions of dollars in renovations were needed to stay at Turner. They showed a map of fans and where they were located. The stadium would be in a prime location for them. Fans from the south side of the city were upset. Traffic became the main concern. Oh, the traffic. Under-the-table deals were made, re-elections lost, jobs changed, parking battles waged on...you know these stories.

Now, the stadium is complete. SunTrust Park is about to open its doors with its first event on Mar. 31, an exhibition game against the New York Yankees. Then, on April 14, its true Opening Day, with a sell-out crowd of 41,000 on hand to witness the beginning of a new era.

It's been a long three and a half years since Schuerholz sat in front of the camera and first talked about concepts of a "mixed-use development," now known as The Battery Atlanta, and a location that would be in "the heart of Braves Country." The cost of the entire project made its way up to $1.1 billion.

But along the way, there are stories that have not been told, until now.

There's the story of the the first game of catch by a boy and his dad's friend in a stadium only half complete, and the story of a general manager tasked with trying to build a competitive team in time for the new stadium after years of disappointment. There are the stories of the Braves players and manager, who have their own feelings about Turner Field, the move to Cobb County and how it affects them. There's the 9 to 5 worker who works across the street from SunTrust Park, who has witnessed the stadium's construction from day one and has sat through days with no power, driven between orange barrels for years, and is still heartbroken at the sight of the turtles trying to escape the demolition. There's the story of a university, that took it upon itself to save Turner Field and now write the historic stadium's third chapter.

SunTrust Park is here, and while you know its convoluted story, these are the stories from some of the people who were most affected by the Braves moving out of Atlanta and to Cobb County.

'A football field within a former baseball stadium within a former Olympic Stadium' The Ted lives on thanks to Georgia State

It was the week of Thanksgiving.

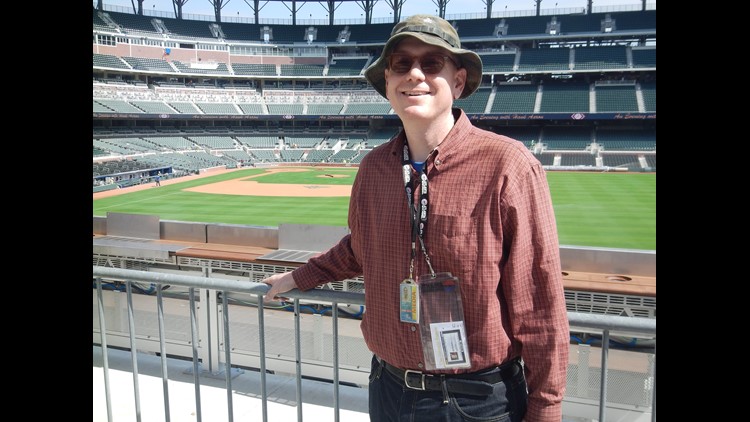

Coppolella was getting a look at SunTrust Park with his family, and he was joined by former second baseman Harold Reynolds and his family. Reynolds played MLB for 11 years and is now a baseball analyst for MLB Network and FOX Sports. The two have been friends for a long time.

There was no grass, no infield. SunTrust Park was filled with dirt and debris from the construction. In about a month, Coppolella would move into his new office with the rest of the Braves front office.

Coppolella witnessed something special. It wasn't special because the days of waiting for SunTrust Park to be built were almost behind him, and not because he could soon begin using the ballpark as a selling point for potential free agents. It wasn't even because he was about to sign Sean Rodriguez to a Thanksgiving day deal.

It had nothing to do with his job.

It was remarkable because Coppolella was witnessing the first moment of baseball inside SunTrust Park. While meandering about, his son and Reynolds began an impromptu game of catch.

"Seeing Harold and my son playing catch while there was still no infield-- it was still being built-- that was something that was kind of special for me," Coppolella said. "It’s something that, as my son gets older, just seeing him there prior to when they laid the grass and before we even moved into the office and he was playing catch with someone like Harold Reynolds, that’s pretty cool."

Coppolella was a dad at that moment. He could envision his family attending the ballpark day in and day out like so many families will do in the future. That moment between a father and son, a family and friends, Coppolella said is an "expectation" he wants all to feel when they are at SunTrust Park.

Coppolella was still transitioning out of scouting and into the Braves organization when they announced the team would be leaving Turner Field. It was almost three years later that he and president of baseball operations John Hart would take over the duties of constructing a team to get the organization back to its glory days.

Move by move, Coppolella executed his plan. He focused on younger, talented prospects, allowing things to get worse while gradually moving the pieces of a rebuild, a rebuild that needed to show signs of progress by the time SunTrust Park opened its doors in 2017.

"When you move into a new park, you want to be good," Coppoella said. "But you want to be good every year."

That wasn't always possible, though. Guys came through the organization and were pieces for Coppolella as he planned his next move towards creating a team that could contend. He specifically mentioned clearing out pieces like B.J. Upton and Chris Johnson to clear salary space while the team, he believed, improved offensively. His plan with that space was to find veteran pitchers, something he would be able to do after the 2016 season and sign Bartolo Colon, Jaime Garcia and R.A. Dickey.

"They were a need," he said. "So we felt like we could build a good, winning team this year."

Up until now, Coppolella has not been able to use the stadium as a selling point while negotiating contracts.

"It will next year. As we start to head into free agency, we can have people fly into Atlanta and see the stadium, see what’s going on there. Whereas this year, it was still being built so they didn’t get to take full advantage of it," he said.

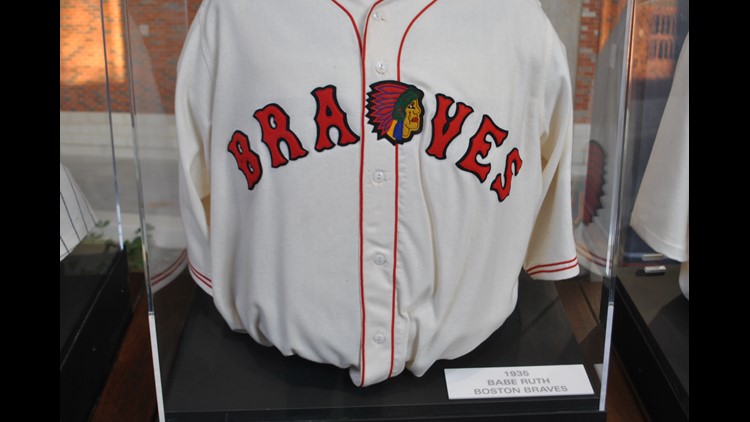

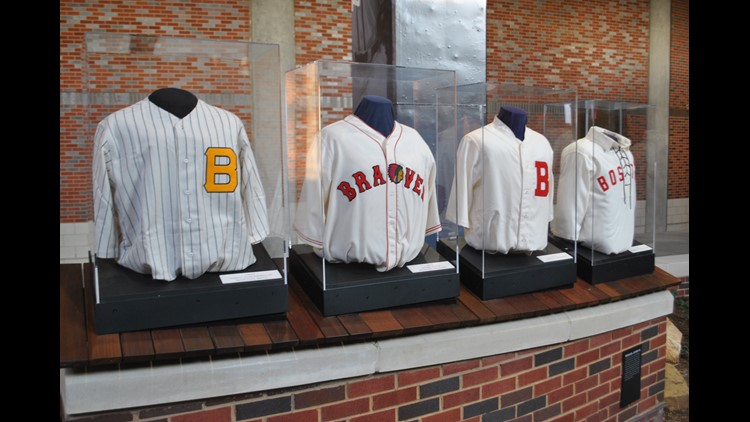

Coppolella has gone back and looked at the Braves when they moved out of Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium to Turner Field. He's quick to point out the team was smack-dab in the middle of its run of 14 consecutive division titles. That momentum is not a luxury the Braves have right now.

"We want to start a new run," he said. "It’s something the Braves organization is directly invested in as we shape this great park. So for us, on the baseball side, we want to try and build the best possible team, not only for 2017, but build something for a long time."

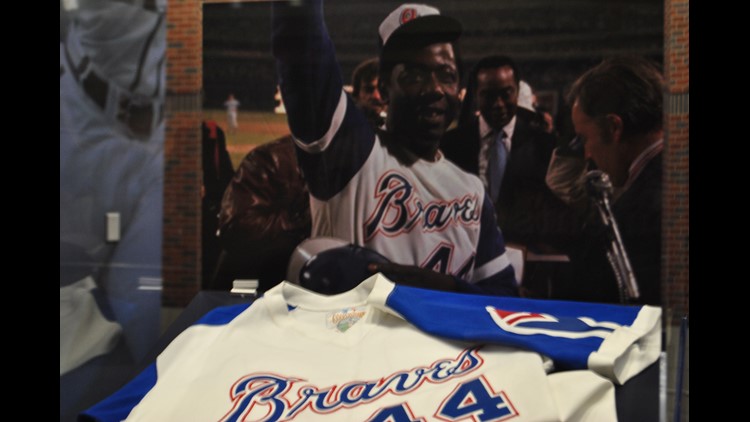

Braves unveil new statue of Hank Aaron at SunTrust Park

Pitcher R.A. Dickey is finally playing for his hometown club.

Dickey has played 14 seasons in MLB, but 2017 is his first season with the Braves. He's from Nashville, and has lived there his entire life. With the Braves being the closest MLB team to the Music City, he became a fan. That's why when the Braves were interested in him this offseason, it was a no-brainer for the 42-year-old knuckleballer.

"It made the decision very easy, and getting to play so close to home for a team I idolized growing up. It’s such a special-- it sounds so cliche to say-- what it is for me is it’s very nostalgic because I grew up watching Atlanta Braves baseball with my dad, listening to Skip Caray," he said.

His childhood dream to play at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium became a reality, but it was a little different than he thought it would be. He played for the USA national team during the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta. USA won the bronze medal that year.

"I remember it pretty well because it was such a highlight of my career. But when you’re that age, you don’t really pay attention like you do when you’re professional. You’re just happy to be there. You’re not looking around much. I threw two games there, and I did fairly well, and we won the bronze medal. I think the things I remember most was getting up on the podium in that stadium and getting that medal," he said.

Dickey also had his fair share of memories at Turner Field, playing there several times when he was with the New York Mets.

"I had a lot of outings on that field. I was pitching an outing for the Mets on that field. I remember one of the games that stood out was Billy Wagner came in, and Jeff Francoeur-- believe it or not-- came in and hit an excuse me, opposite field home run, and I remember I won the game because of it. It was an accident. He came back in the dugout and said, ‘I don’t know how I hit that. It just went out.’ I remember little moments like that on that field," he recalled.

Ironically, Dickey never got to pitch at either stadium in a Braves jersey. But he will take the mound at SunTrust Park, finally wearing the Tomahawk on his chest and the A on his cap. Dickey will take the mound at SunTrust Park during its Opening Week. Then, he will have pitched at all three Atlanta Braves stadiums.

"Knowing it was going to be a new stadium, you knew it was going to be done well," Dickey said. "I think where it is is very appealing to me. You didn’t have to get into the heart of the city to fight all the traffic for one. But it’s north of the city, it’s that much closer to Nashville."

Dickey isn't the only hometown guy joining the team during the start of the SunTrust era. Brandon Phillips recently joined the roster. He went to Redan High School in Stone Mountain.

Ironically, Phillips did wear a Braves jersey at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium. But he was 16 then, and he was a bat boy.

"Just growing up being a Braves fan, that was the number one thing. I never thought the Braves would be interested in a Georgia boy such as myself, but when I got the call, I was like, boy, this is going to be something epic, it’s a blessing in disguise," Phillips said on getting traded from the Cincinnati Reds after playing there for 11 seasons. "The only time I really ever wore a Braves jersey was when I was 16, and I had to work out at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium. And one day I looked at myself in the mirror and said, 'I’m going to wear this jersey.' Look at me now."

Like Dickey, Phillips played at Turner Field, but always as a Red. When he got the call about coming to Atlanta, SunTrust Park was the last thing on his mind. He was thinking about moving, especially with his 3-year-old, Micah, who is obsessed with No. 4, Phillips' number.

"He’s just looking forward to seeing daddy wear a new jersey. He’s so used to daddy wearing red all the time. He’s like, ‘Daddy, you’re not on the red team anymore?’ So it’s just little cute things like that," Phillips said.

Phillips lives near SunTrust and passes it frequently. Now, the stadium is more prominent on his mind. It's also on Micah's mind.

"He’s looking forward to the new stadium. He’s seen pictures of it. When we drive by, he always sees the stadium also with the lights, he’s like ‘Oh, look at it. Look at the lights.’ "

PHOTOS: Media gets advance look at SunTrust Park

The Braves have some work to do.

They've never hit, pitched, run the bases or done anything at SunTrust Park. When they visited before spring training, there wasn't even grass. They will head into the season with very little home field advantage.

In a way, it's like the first day of school. They will have to figure out where everything is and figure out their routine. Outfielder Nick Markakis even said they've got homework.

"You know, that playing surface isn’t going to play like every ballpark. It’s going to have its certain hops, and you got to go out there and do your homework. And eventually along the way, you’re going to learn more and more about the new ballpark and your surroundings," he said.

It's true. The outfield grass is now Seashore Paspalum, which was used only in the infield at Turner Field, and the outfield grass there was Bermuda.

"We do it to improve playability, and they'll get the benefit out of it," Ed Mangan, the team's field director, said.

The Braves front office from time to time would ask the players on their input on small things during the planning process, according to Markakis. "They did ask our input and ultimately we’re the ones on the field so we’re the ones that got to go to work everyday."

So now that the "workers" have everything they need, do they feel the pressure now to win, especially after three seasons without a winning record or postseason appearance?

"You try to eliminate those things and take it like it’s any other ballgame. Whether it’s a new ballpark or an old ballpark, we’ve still got a job to do. We’ve got to go out there and win as many games as we can," Markakis said.

Manager Brian Snitker is the man the Braves decided to lead the team into the SunTrust Park era. He took over after the club fired Fredi Gonzalez early in 2016. Snitker said there's always pressure when the uniform is on.

"It’s always good because a new stadium always brings out new people to want to see you. Consequently you always have a lot of big crowds, and that’s good. There’s always an energy when you have a big following and guys are following. The stands are full and are energized, and players feed off that," Snitker said. "I know we’re professional, but you can’t help feed off of that, the energy that a fan base will bring."

For Snitker, a new ballpark doesn't mean much to him as far as his routine is concerned.

"I moved up there so maybe I don’t have to go up to the park so early," he said. "I don’t know if your routine probably changes year to year. As I’m doing this job, it’s going to get different and different, too."

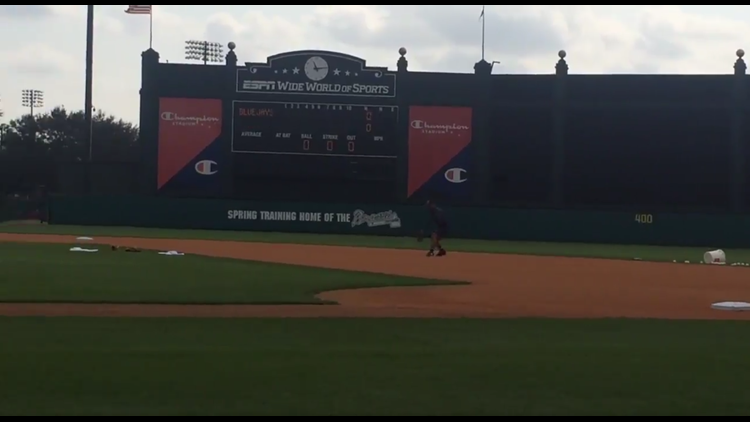

Photos: Braves report to Spring Training

David Barstow likes his new neighbors, but they've been moving in for about four years now. He's ready for them to finish.

Barstow works at an online company in the 1100 Building on Circle 75 Parkway. His company moved into that building five years ago. It was only a year later when the Braves announced they would be moving directly across the street from where he works.

"When it broke that morning and we all came in to work and said, ‘Is this really -- Is it at a joke? Where exactly are they going to put it?' " he said.

They would put it where there used to be a vibrant green space. Barstow remembers there was a lake, trees, ducks and turtles. He said there would be about 20-30 people out there in the afternoon at lunch time. Soon enough, the lake was drained, the trees were chopped and the demolition began. Barstow remembers the turtles frantically trying to cross the road as the construction began. It was time for them to find a new home.

What began was roughly four years of construction, which included blasting, road closures, and Barstow fighting to find a parking spot with the construction workers who would park in the building's deck. But Barstow made the best of all of it.

"Kind of have to figure out on a daily basis what lane I’m supposed to turn into and how many trucks will be in front of me," he said. "Whether or not the construction worker looking at his phone when he steps out onto the street is going to realize that I’m coming at him at 35 miles per hour, but once I’m in the building, they’re good neighbors."

On blasting days, Barstow made it a family affair, inviting his kids to watch from his 14th-floor office, which overlooks almost all of the outfield and first-base side of the park. The Braves would send emails warning about the blasts, which was helpful. But Barstow said they weren't always that communicative.

"There’s been at least four or five power outages on this whole block," he said, "That have sometimes gone on for eight or nine hours before power is restored which definitely causes us to work from home."

More than anything, Barstow is ready for the whole development to be completed. He's a Braves fan and is excited about being able to walk to a game from work. He's also thrilled to have somewhere he can walk to for lunch other than the 2nd-floor cafeteria in his office building.

What about traffic? Barstow isn't worried.

"There’s some level of concern but at the same time…with the development that’s going to be adjacent to it, I think arrival times for Braves fans are going to be greatly staggered," he said. "So it’s not going to be the same as Turner Field where basically there’s no attraction so everyone comes at the same times and leaves at the same time."

However, if he and the other workers have to say late, he knows there will be an issue. He hopes the Braves have fully addressed those possible issues by widening the road and adding stop lights.

"I think for the most part, people don’t work in this area so they don’t know how bad the construction has affected us. I feel like the construction is worse than any game day is going to be."

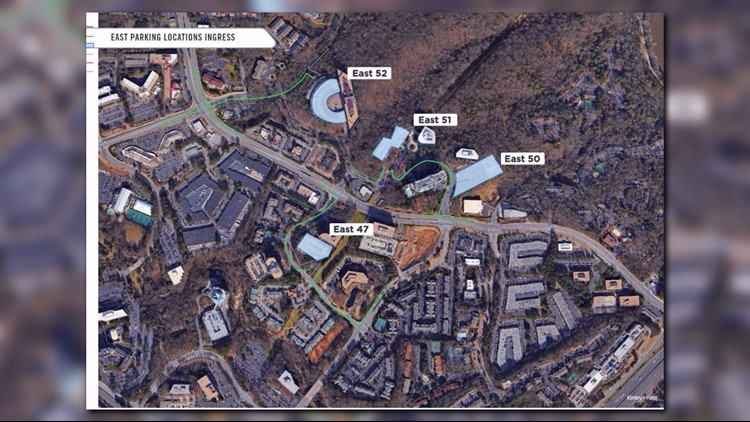

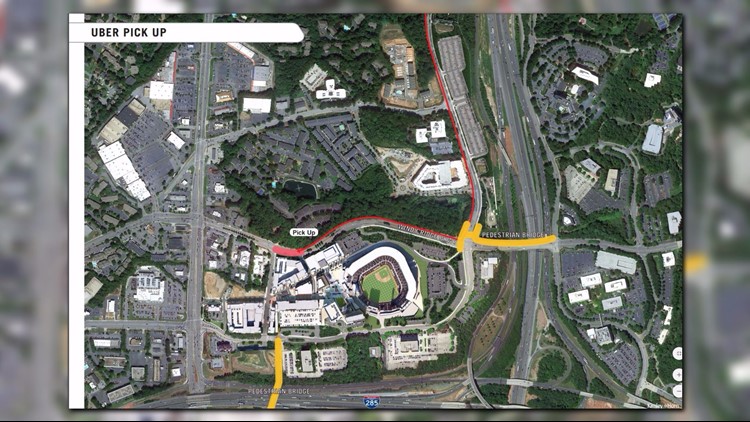

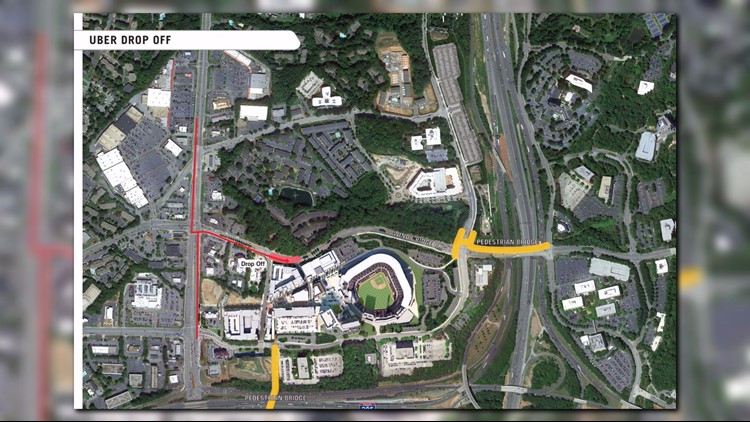

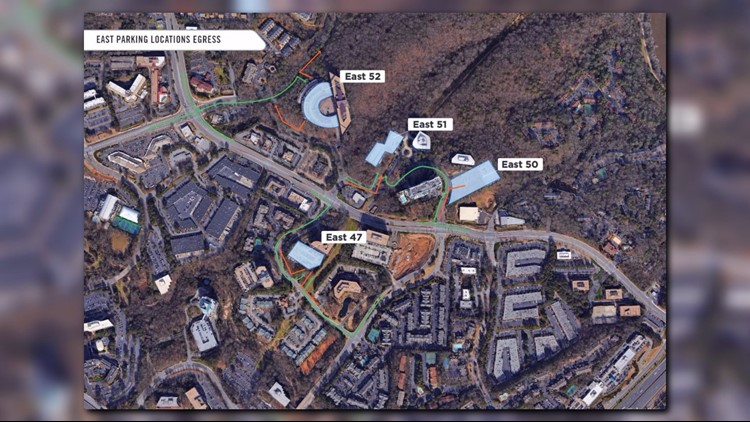

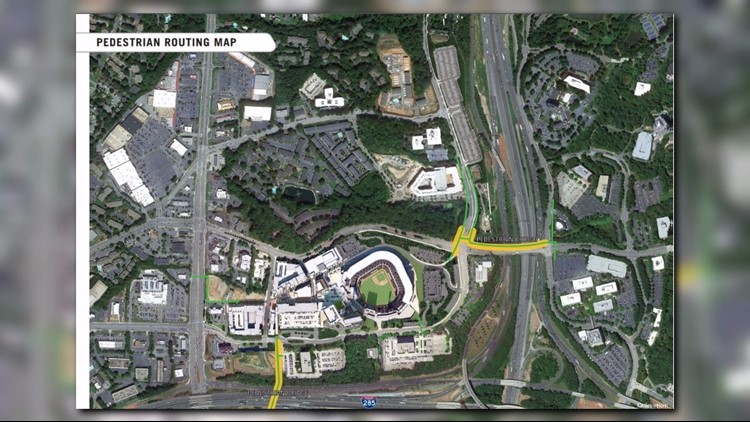

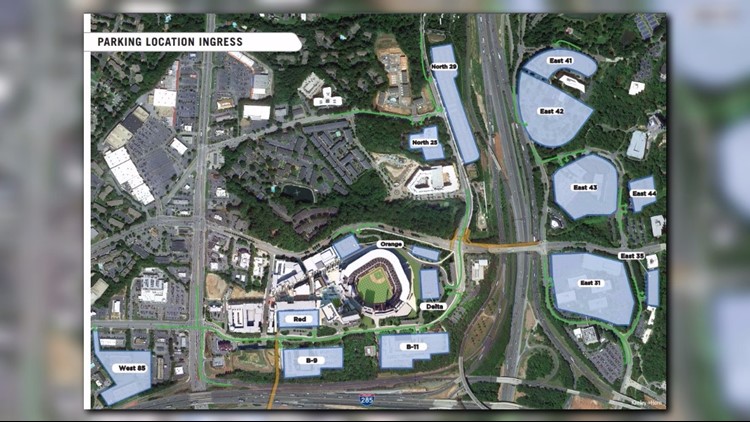

PHOTOS: SunTrust Park transportation plans

Charlie Cobb was starting another day at Appalachian State.

Even though it had been a while since he had lived in Atlanta, he still checked up on Atlanta news almost every day. On the morning of Nov. 11, 2013, there was a headline that caught his eye: The Braves are leaving Atlanta.

When Cobb realized that Turner Field was going to be abandoned with no foreseeable future, he knew what needed to happen. A college nearby, Georgia State, needed to get it.

"When I saw the stadium, I knew right away what needed to happen with it. It was a big spur of why I came to Georgia State and to be the director of athletics was to be a part of this project," Cobb said.

About a year later, Cobb was hired to be Georgia State's athletic director. The university had already publicly said they would be making a pitch to the city to acquire Turner Field and its surrounding land to retrofit the baseball stadium into a football stadium, build a baseball stadium at the sight of Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium, and build mixed-use developments on the surrounding land, working with the developer, Carter, all costing about $300 million.

After fighting their way to the front, going up against casinos and companies wanting to build warehouses where Turner Field is, finally the city made its decision. University President Dr. Mark Becker gave Cobb the good news.

"When President Becker called me to tell me it was a done deal, the Recreational Authority was going to sell the stadium directly to the university, I think that’s when the finality for me hit. What we thought about for almost two, three years, it really came to fruition and now we get a chance to put this in order," Cobb said. "It was just a lot of euphoria. You had a sense it was inevitable."

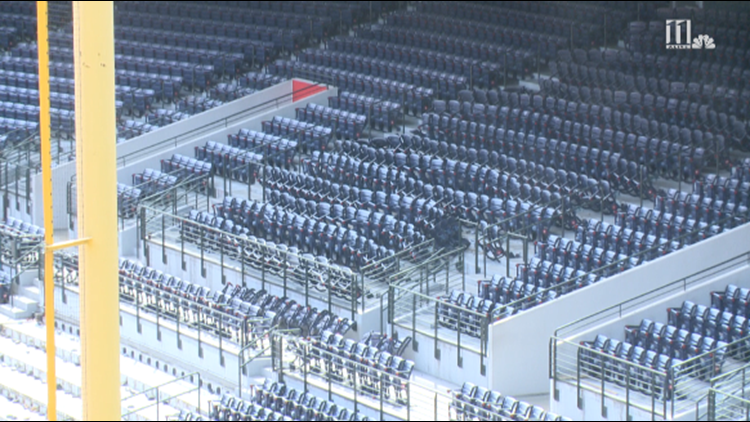

Georgia State took over the land in January after purchasing it for $22.8 million. Construction began in February. They've knocked out sections of seats to make room for end zones and are quickly working for a home opening debut against Tennessee State on Aug. 31. Going into their eighth season of football, the program hired its third head coach, former South Carolina assistant coach Shawn Elliott. Already, Georgia State is reaping the benefits of moving into the former home of the Braves.

"Anytime you lease something and it’s not your own, I don’t know how much pride you have in it," Elliott said, referring to when Georgia State would lease the Georgia Dome to play in. "It probably had to be awkward."

Elliott has already hosted recruiting events at Turner Field, now referred to as Georgia State Stadium, to allow them to witness the construction.

"They’re star struck, just to look at this facility and then telling them the plans," he said. "The guys just have bright eyes and they look around and you say, ‘Yeah this will all be yours.’ "

Cobb said it is all thanks to the Braves.

"We've seen the benefit from the Braves playing here for 20 years. Our coaches went recruiting this fall, especially kids who are familiar with downtown, most of them have been to a Braves game, their parents have been with them for a Braves game. So, it answered the question of familiarity. So as we do the conversion and turn it into a football facility, give it a new name, it only helps us," Cobb said.

While Cobb's goal is to create a home for the Panthers that feels authentic and compares to other college football stadiums, he does not want to completely destroy the stadium's historic legacy. Cobb has worked on four stadium projects in his history as an athletic director at N.C. State and Appalachian State. While it's one of the biggest projects he's worked on, he doesn't regard it as the most challenging.

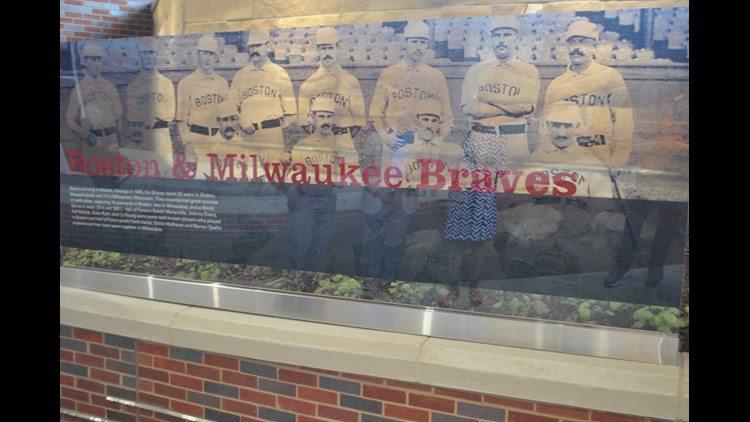

"I’d say it’s one of the more fascinating. Again, because there’s so much history in this stadium. It’s probably a weekly experience that something new pops up that is either a legacy from the Olympics or is a legacy from the Braves, and then us trying to do this conversion to turn it into a football facility primarily," Cobb said.

"It’s a great story to talk about the Olympics and all the great things the Olympics did for Downtown Atlanta," he said. "I think the Braves are the same way with that their history means to this area and this part of downtown and the community. I think we will write that third chapter with the university."