ATLANTA — The Heat Island Effect is when some parts of a city are much hotter than others. Temperatures can widely vary, as much as 10 to 15 degrees in difference throughout the day and night.

Why does it happen? Because cities like Atlanta are big and expansive with a variety of land uses and surfaces.

In residential areas with single-family homes, and tree-lined streets, the lush tree canopy can help to keep those areas cooler throughout the day and night. But in contrast, in the middle of the "concrete jungle" of Midtown and Downtown, the concrete, asphalt, and buildings absorb and re-emit heat throughout the day and night. This keeps those areas much warmer.

At the University of Georgia, Dr. Marshall Shepherd has been studying heat islands in the state for more than a decade. In his research, they used satellite data to see which parts of the city are the hottest.

But as his research progressed, one stark piece of data kept sticking out.

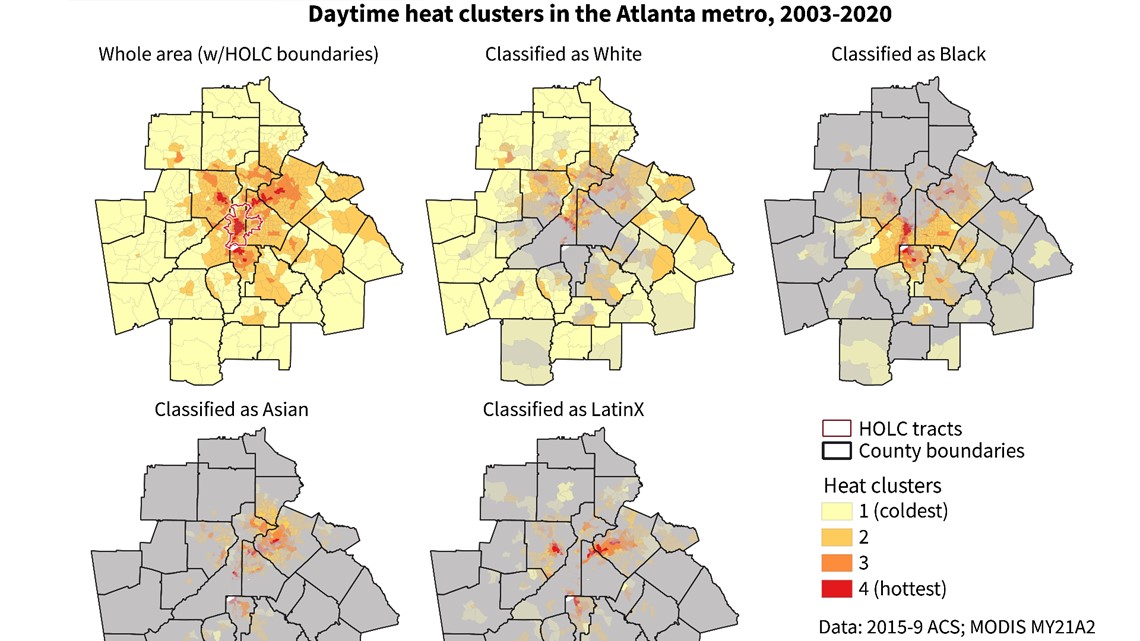

"What we found is that certain populations, particularly communities of color and some of our poorer communities are disproportionately living in the hottest parts of Atlanta's heat island," Shepherd explained.

To show this, they extracted the heat data and aligned it with the primary race in different neighborhoods of the city and also aligned it with the hottest daytime temperatures from 2003 to 2020.

They found a strong correlation between Atlanta's biggest hot spots and areas with were historically redlined in the 1930s.

"Our analysis shows that clearly, those hottest areas aligned very closely with those grades in the HOLC categories associated with redlined communities," Shepherd said. "So the grades that were lowest were the communities that were most redlined. And the most redlined areas... historically are the hottest since 1940."

Shepherd refers to this as heat injustice.

But he wants to make the next phase of this research how to fix this inequities. He's coined the new term "thermal justice."

There are some simple ways that are proven to help cool the hottest places in a city, like adding more trees and parks, changing the colors of pavement from dark to cooler, like concrete.

But to really tackle the disproportionate heat as our climate continues to warm, Shepherd said city planners will need to go further than that.

"We've proposed radical new ways to engineer cities of the future to redistribute and repurpose this heat," he said.

They're waiting to secure funding for that next phase of research, which would also involve colleagues at other colleges and universities, like Georgia Tech.