The unforgotten

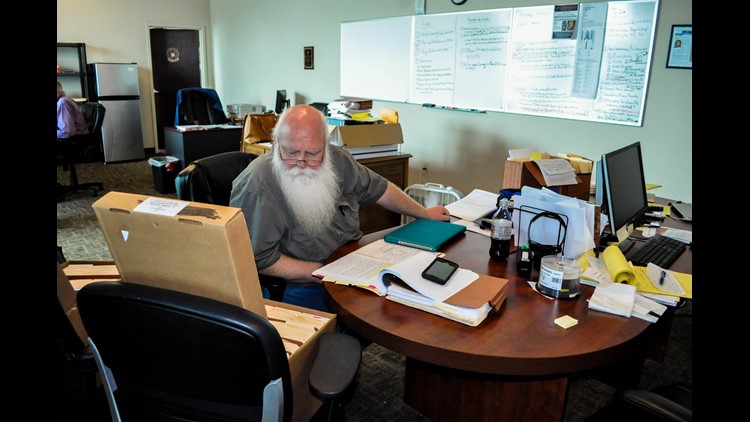

MARIETTA, Ga. – Nestled inside the Cobb County Superior Courthouse is a modest room in the back corner of the second floor. The walls are lined with framed accolades, inspirational quotes and box after box stacked to the ceiling, filled with cold case files. It's where the forgotten are remembered, questions are answered and cases are finally solved.

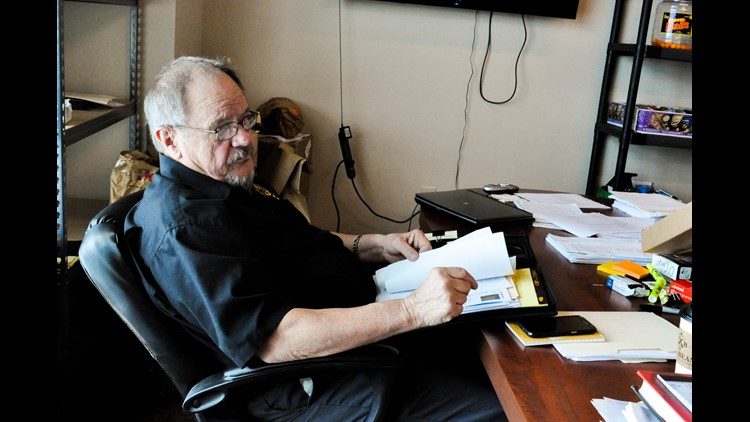

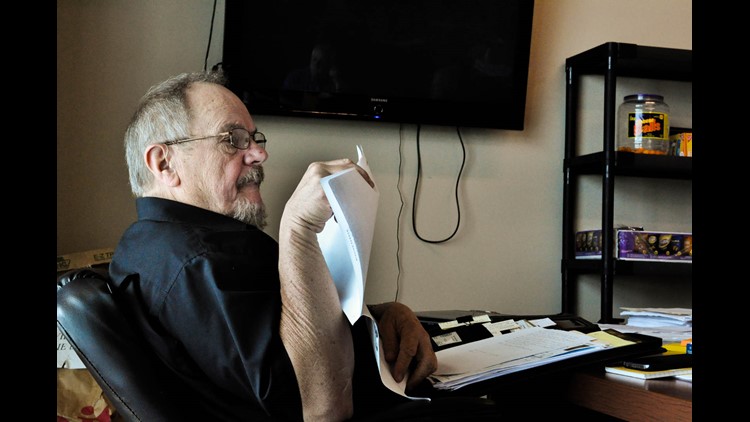

“My drive, the reason I wake up in the morning ready to go, is because every case that we have in here represents a family that needs an answer,” said John Dawes, director and lead detective of the Cobb County Cold Case Unit, aka "Charlie 4."

In Cobb County, Ga., there are more than 90 cold cases sitting on those shelves, waiting to be solved—the oldest dating back to 1972. To some, it may seem like a daunting, unforgiving task, too mountainous to fathom completing.

Not for these detectives.

Digging deep, solving cases… it’s in their blood. It’s a part of who they are. It’s a calling they cannot deny—even after retirement.

The unit, created by Cobb County District Attorney Vic Reynolds, is made up of a tight-knit group of about a half-dozen detectives. But they aren’t necessarily spring chickens—all retired from law enforcement or the military. They still have a fire inside of them that can match any rookie investigator and then some—and they double down with decades of experience nabbing the “bad guys” off the streets.

Above them on the third floor, is Reynolds, who’s prosecuting the cases they’re cracking—some decades later.

“They do it because of a passion and a dedication in making sure that these victims' families figure out and understand and know what happened to their loved one, and primarily to make sure that the people who commit these crimes are eventually brought to justice,” Reynolds said.

One of those families once tucked inside a cold case file box is the Castlins’ story.

Closing the file, healing a broken heart

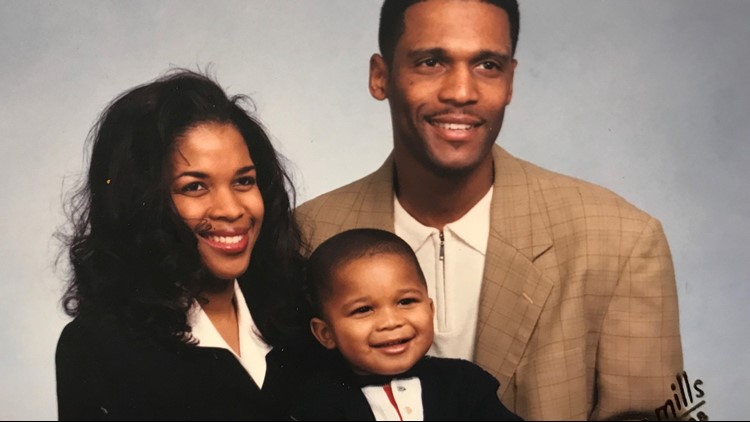

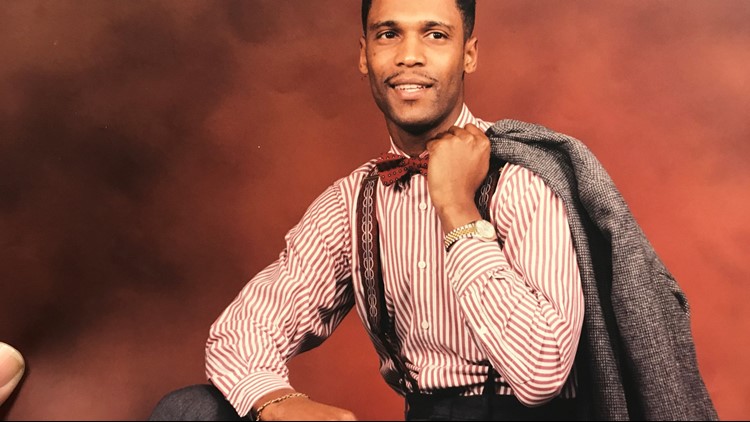

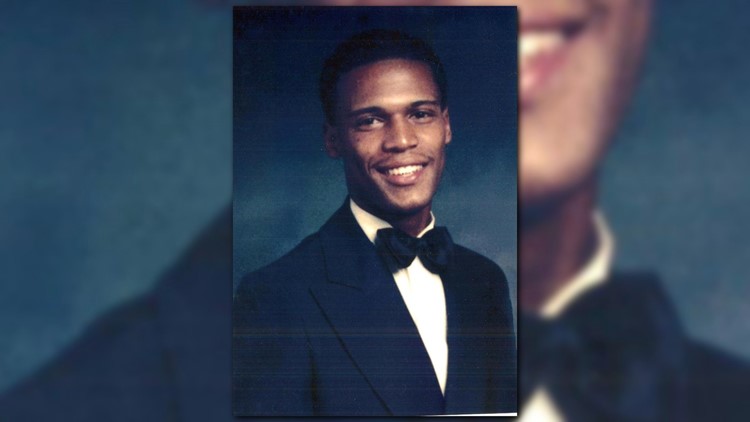

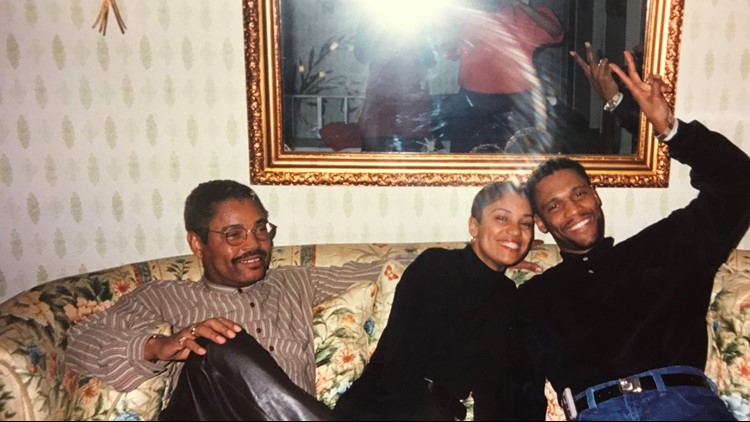

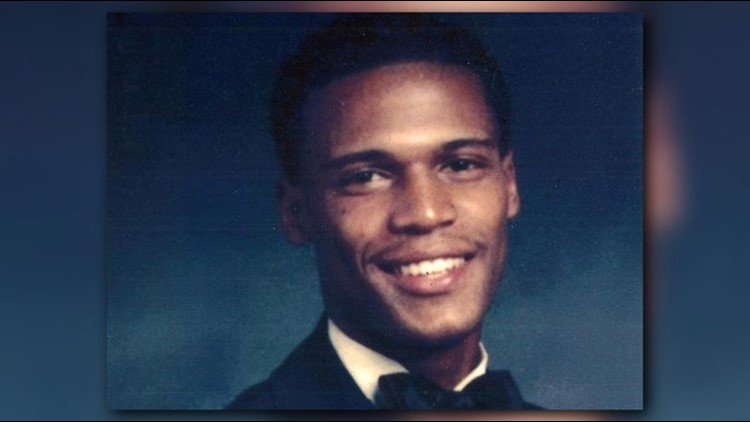

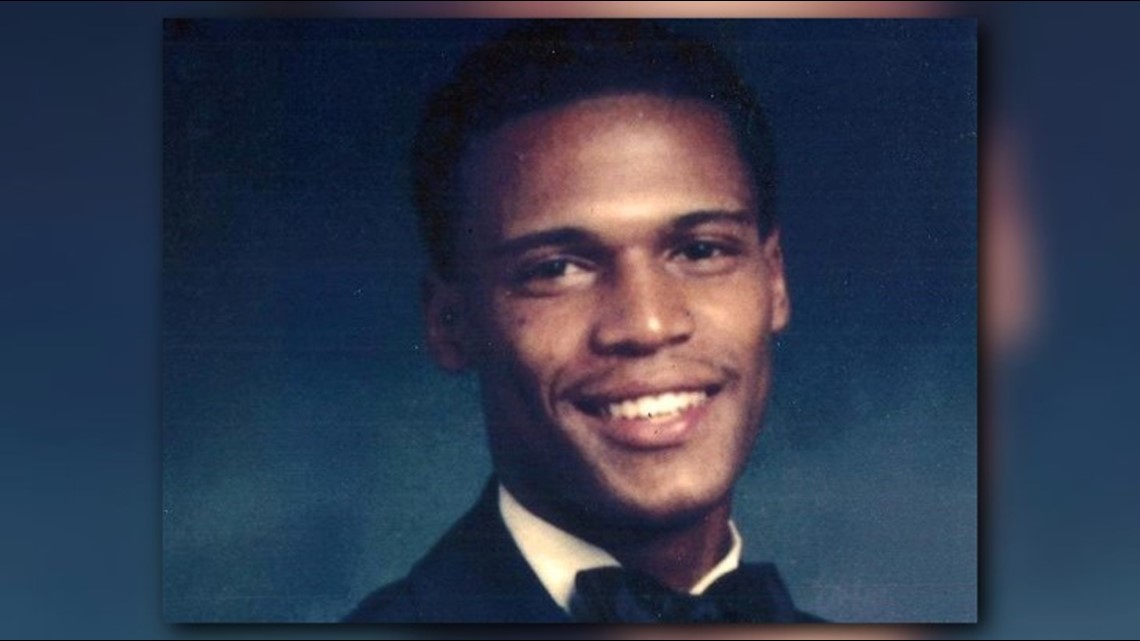

Kelley Castlin-Gacutan, 47, gently traces her dapper husband’s face with her finger on a photograph of him smiling, and sharply dressed in a black tuxedo.

“He loved us so much; he loved family. He loved life. He was ambitious. He was funny, smart, very good looking.”

Every single day, she hears his laughter and his calming voice, “Just wait and see… you’ll see.”

“He was wise beyond his years,” Kelley remembered, beaming with undeniable pride.

“He would just tell me, ‘You'll see. You just keep on living, you'll start to see some of these things that I'm telling you about.’”

One day, he told her, “People change. Life changes. Things are not always going to be the same.”

Kelley, then-31, could not have realized that one of those changes would be not having him in her life.

“Rodney was such a good person—I mean, probably one of the most painful things, when I think about how he left us, is that I know that he was thinking of us when he saw that person put a gun in his face. I know that.”

PHOTOS | Solved: Rodney Castlin murder

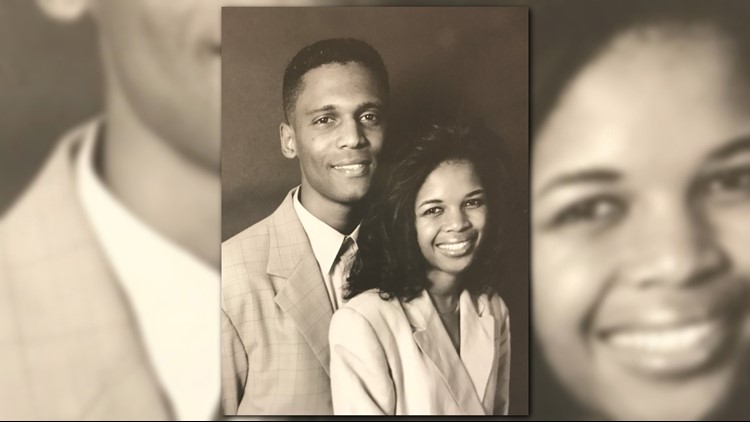

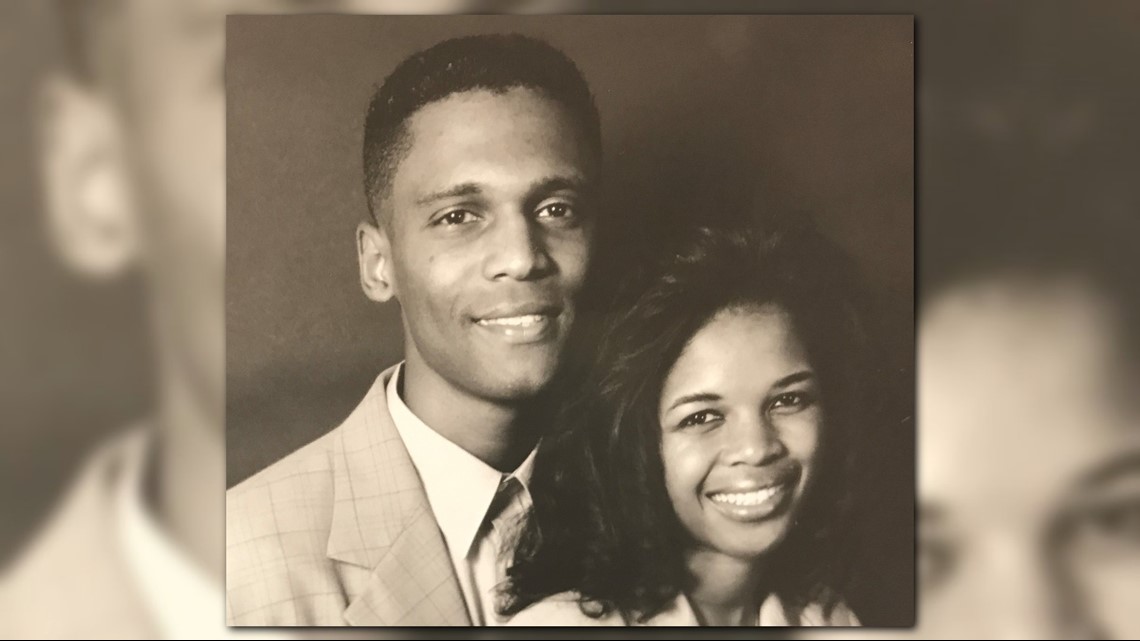

Rodney and Kelley met in the fall of 1991. Their love story was a whirlwind.

Rodney was working for an insurance company and she worked at a bank—both within the same office building.

“A person who worked in the building kept telling us about one another and one day we met in the lobby,” Kelley recalled.

Shortly after, they went on their first date. He came to her apartment, she said, and they sat and talked for hours on end.

“I knew he was the one for me because we were the best of friends,” Kelley said. “Our connection was even evident to people who were around us. He meant the world to me and I know he felt the same.”

A few years after they began dating, Rodney proposed to her at her favorite restaurant at the time: Red Lobster.

With a classic black and white theme, the couple married on April 5, 1995 with a 16-person wedding party, as well as their family and friends to help them celebrate.

With a black tuxedo, complete with a white bow tie and shined black dress shoes, Rodney posed in photos next to his bride, Kelley, who was wearing a delicate pearl and lace head piece, matching a fitted, lace-adorned white gown with a sweetheart cut and satin train.

But on Thursday, Dec. 7, 2000, the Castlin family’s fairytale life would take a dramatic detour and change their lives forever.

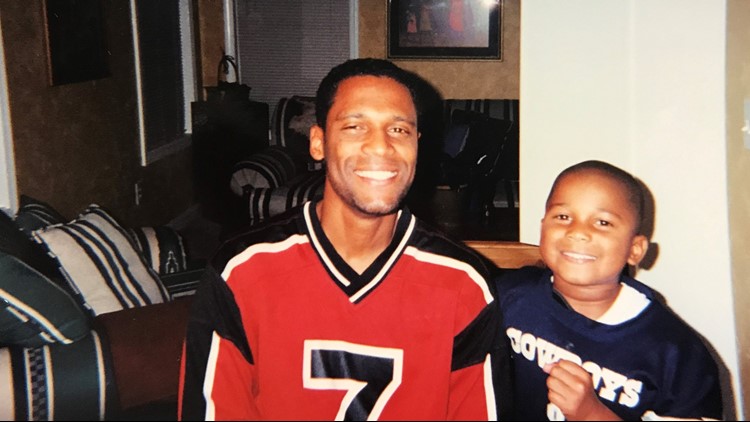

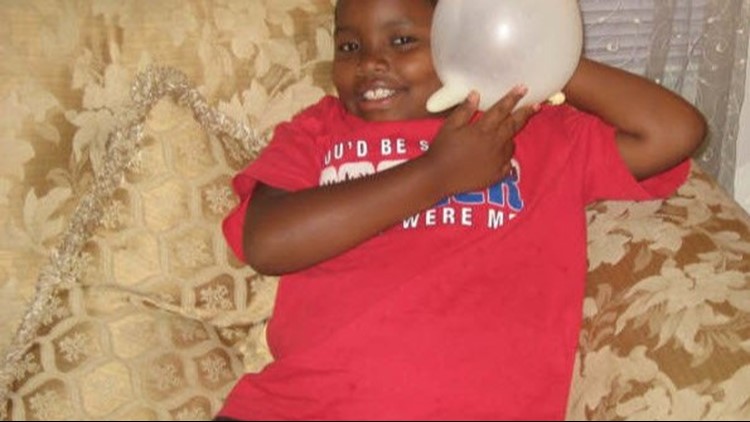

Rodney, 36, took classes during the day and worked as a hotel manager at night, working toward a business degree at Chattahoochee Technical College— his goal was to open his own business detailing cars.

“We were just a very happy couple, just looking forward to brighter days,” Kelley said, after losing a child a year earlier.

On a chilly winter evening, just before Christmas, Kelley remembered that she and their 4-year-old son, Kyle, had pizza for dinner and before going to bed, she called Rodney, who was already at work at the Wingate Inn—a business-class hotel in Kennessaw, Ga., just off Interstate 75, that had only been open for about six months.

He had started at the nearby Days Inn and worked there a year before moving to the newly-opened Wingate--now a La Quinta Inn--taking a position as the night manager.

The young couple spoke around 8 p.m.

Kelley, who was an assistant principal at a local school, remembers it as a brief conversation, just a typical recap of what each other had done that day—especially since they were on conflicting schedules—her on days, him on nights.

When he worked nights, she said, it was always important for them to talk before she went to bed.

“You just never know what the day brings,” she said.

That night, while she talked to Rodney, he told her about the audit that he had coming up the following day and how he was preparing for it. It was a busy night for him.

She told Rodney she was going to get Kyle ready for bed and that she was going to go to sleep as well.

“Our last words were, ‘I love you,’” Kelley said.

At approximately 11 p.m., Kelley was startled awake by a knocking on her front door.

“I thought I heard someone at the door... and I thought, well, Rodney must have forgotten his garage door opener. I went down the stairs and at my door was sheriff's deputies,” she recalled.

They asked to come inside her Acworth home. Catching her breath, she cautiously obliged with confusion about why they were there.

Then-Cobb County detective, Dawes, divulged to her the worst news of her life.

“We want to let you know that there was a shooting at the hotel tonight and Rodney was shot and killed,” he told her.

The 8-months pregnant wife and mother’s mind began to swirl in utter disbelief, gasping for air and grasping for answers.

“It was awful. It was awful,” she remembered. “It was extremely painful. I had to do the best that I could to compose myself.”

Amid the chaos and panic, a calming presence came over her. She believes it was Rodney.

“Because of his faith and because of his love for us, I know so well, that I felt comforted by him. So, while it was excruciating, extremely painful, I found a way to cope, even at the onset, because of those factors. It wasn't just me; it was me, having an unborn baby. Me, losing a child. Me, having a 4-year-old—and it is just me now."

Before she knew it, her living room was swarming with people—investigators, neighbors. Kyle woke up and crept downstairs to see what was going on.

“That little 4-year-old looked at me, and he said, ‘I have to take care of you and the baby,’” Kelley remembered.

That night, Dawes made a promise to her.

“We will find the person who killed Rodney. You can count on us to do that. We're not going to give up until we find the person who did it.”

“Day after day, I would call and say, ‘Do we have any leads? Do we know anything?’” she said.

Soon, instead of calling every day, she started calling once a week. Once a week turned into every couple of weeks, to once a month—only to get the same answer: No leads.

“It was very frustrating. It was just incredibly difficult,” she said of not knowing.

But what detectives did know was that at 10:30 p.m., on Dec. 7, 2000, two men busted into the Wingate Inn, near Barrett Parkway.

One of the assailants, who was armed, vaulted over the counter, while the second perpetrator made his way inside a small office near the front desk and robbed a hotel guest.

The young, thin man pointed a handgun and demanded cash from the front desk.

During the chaos, Rodney, who was scheduled to clock out at 11 p.m., emerged from the back office.

That’s when the gunman confronted him about the hotel’s safe.

But, to his detriment, there was no safe in the hotel.

The armed man returned to the front desk and clocked the desk clerk on the back of the head with his .22-caliber handgun, knocking him unconscious.

The man then shot Rodney, striking him in the chest. The bullet exited just below his shoulder blade, and was later recovered from the floor.

The two robbers fled to a car waiting outside, with barely more than a mere $300.

The clerk and the robbed guest sought help, as Rodney laid bleeding, dying on the floor.

The father and husband was pronounced dead on arrival at Kennestone Hospital.

“This was a young man who was literally doing everything that he should do in life. He did everything that we ask of other members of society to do to become productive,” Reynolds said.

Taking a life, serving multiple life sentences

“A precious life was taken from us,” Kelley said.

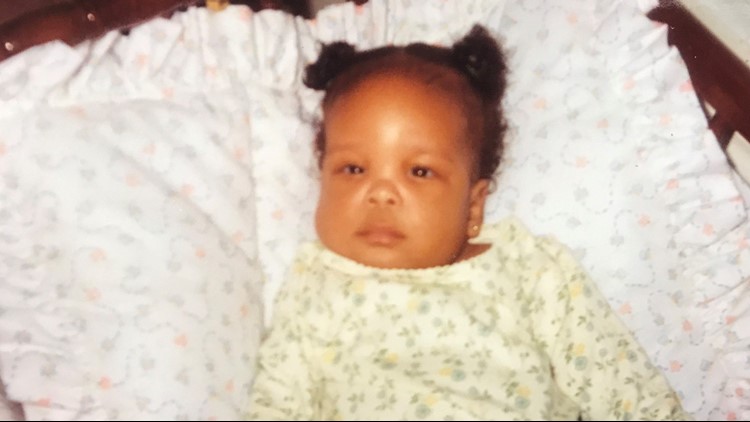

The then-expectant mother said that she bottled up her emotions the best she could following his death. She gave birth to their healthy daughter, Ryan, on Feb. 2, 2001 without Rodney by her side—a daughter who would never know her father and the positive, outgoing person he was.

“He loved people... someone you want to be around, who you want to know. He was a man of faith and he loved his family. He was all of those things and when I look at our children, I see so much of him in them. They are such a reminder of who he was as a person in their own way,” she said.

But she believed that one day, his case would be solved—and the responsible brought to justice.

The Cold Case Unit got the case once it opened their doors, and started looking at the evidence again.

Cobb County Police had processed the scene in 2000, and in doing so, lifted a palm print, which was run through Georgia’s fingerprint database. They ran it again in 2005 and 2009—but to no avail. At that time, police agencies had limited access to the FBI’s fingerprint database, according to Dawes.

But in 2012… a hit.

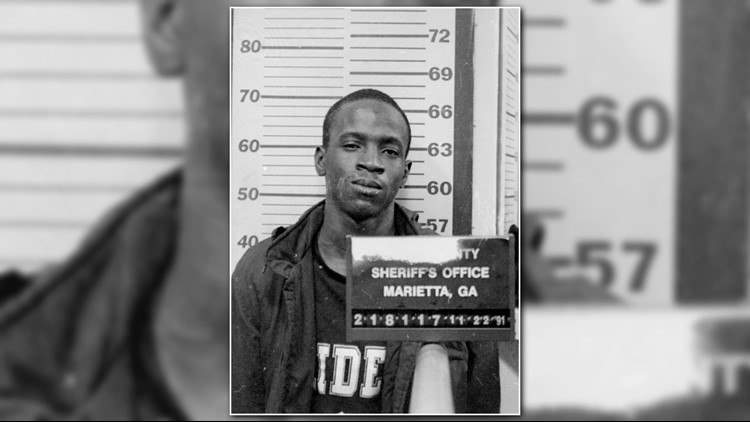

Dawes, who was the case's original detective, identified a suspect, thanks to the perpetrator’s ongoing southern crime spree the same year Rodney was savagely murdered.

According to Dawes, the suspect had left a fingerprint at a South Carolina fast-food restaurant he robbed by gunpoint just after the armed robbery at the Wingate Inn. He was arrested in 2000 for that South Carolina crime and released 10 years later.

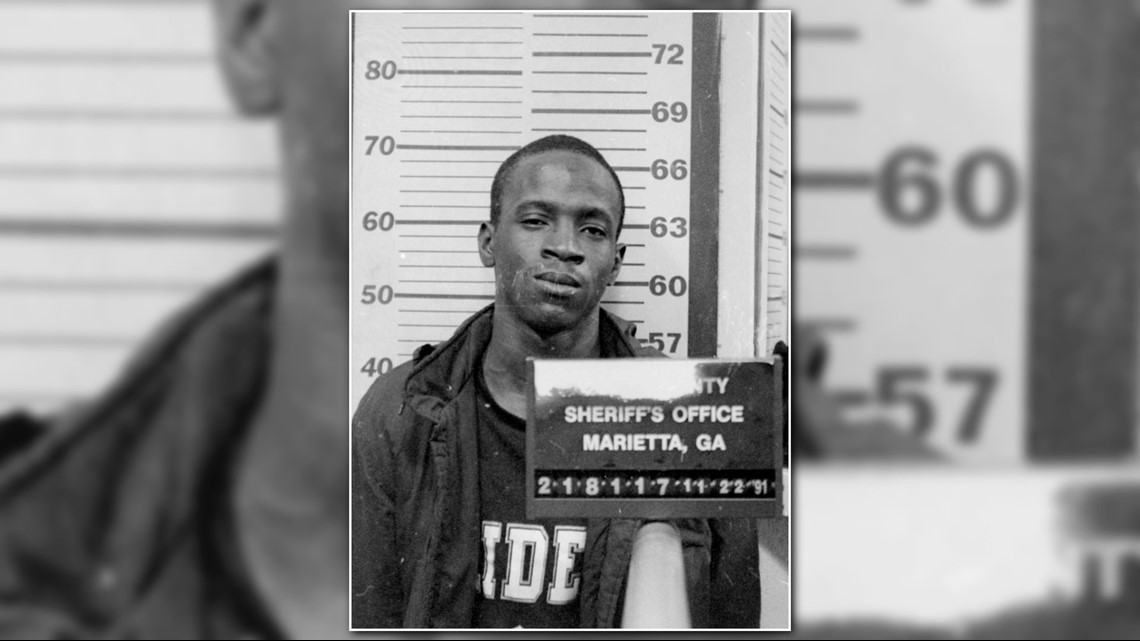

Two years following his release from prison, his fingerprint was run through the national database. It was a match for James Lirenzo Randolph.

Cobb County Police fingerprint experts examined the print from the hotel to the known print of Randolph and determined it was, in fact, a match for that crime as well.

Other evidence, Dawes said, also corroborated that Randolph shot Rodney during the robbery in more than a decade earlier.

In 2014, Kelley’s phone rang at work in Macon, Ga.

Her phone displayed a Cobb County area code.

She held her breath and listened carefully to the husky, raspy voice on the other end of the phone.

“We found the person who killed Rodney,” the man told her.

It was Dawes.

He had kept his promise 14 years later.

Kelley held the phone to her ear in disbelief and as a sudden rush of relief came over her, tears flooded her face.

“I just cried and cried and cried. It was such a relief. I was so happy. And what was really so beautiful in that, is that he kept his word.”

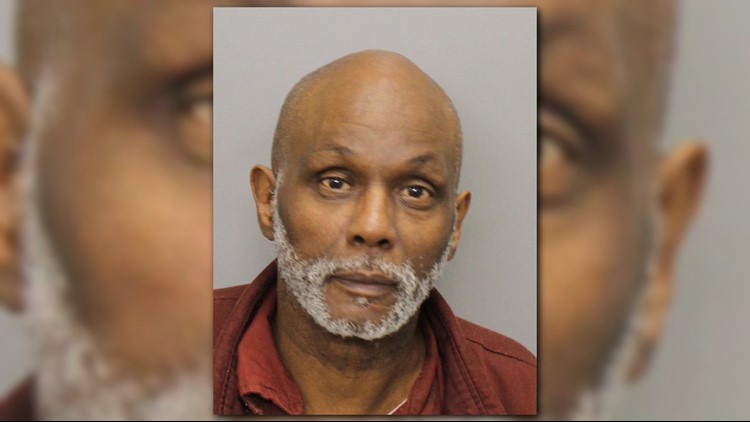

In October 2014, Cobb County Police charged Randolph, then-34, and U.S. Marshals arrested him in Richland County, S.C.

“We just really want justice to be served. I would like a sentence of life without parole, to make sure that no other family has to experience what we went through,” Kelley said leading up to his trial.

But she received more justice than she had hoped for.

Sixteen years after Rodney’s murder, Randolph went to trial.

After sentencing, Kelley remembered, Randolph spoke to the court.

“He spoke about understanding how we feel because he's lost people in his life. I just feel like there is such a disconnect—I don't know what someone in his shoes... I don't know what they go through, what their thoughts are, and how they can commit such an act.

“I can say that I would have liked for him to offer an apology, but I can't say that I expected anything in particular,” said Kelley, who didn’t miss a minute of the trial.

But no apology was uttered for his role in her husband’s brutal murder.

“I can’t do nothing about the past,” Randolph said in court. “I feel they [sic] pain. … I apologize that they lost a loved one. I feel how they feel because I lost two loved ones.”

Randolph was convicted in May 2016 of malice murder, felony murder, criminal attempt to commit armed robbery, two counts of armed robbery, aggravated assault and possession of a firearm during commission of a felony.

Cobb County Chief Assistant District Attorney, Don Geary, who prosecuted the case, sought the maximum punishment on each count.

“This gentleman is a criminal. If we let him out, it’s not if he’ll hurt someone else, it’s how soon. … This man has proven that he’s someone the public needs to be protected from,” Geary said to the judge.

Cobb Superior Court Judge Robert E. Flournoy III agreed and sentenced Randolph to three consecutive life sentences, plus 35 years.

“I always thought, one day... I didn't know when, obviously, but I felt like, one day there has to be an answer as to who did this. And I'm just so grateful to have been here to witness it,” Kelley said. “We really had closure; justice was served.”

The Castlin case was the Cold Case Unit’s first solved case.

“When I think about this team... all of those who come back and give of their time and their talent to work on cases like this, I am incredibly grateful,” Kelley said. “I'm grateful because when someone commits crimes like that, is still out there, the safety of others is at risk. And I never want anyone to ever have to go through the pain and agony of what our family had to go through.”

“I'm just grateful to have known [Rodney]. He was my best friend; he was a loving father; he was an excellent husband. And I don't miss an opportunity to tell our children about how wonderful he was, because it's important to me that our children know about their dad,” Kelley continued.

Lead bulldog: Never give up, never let go

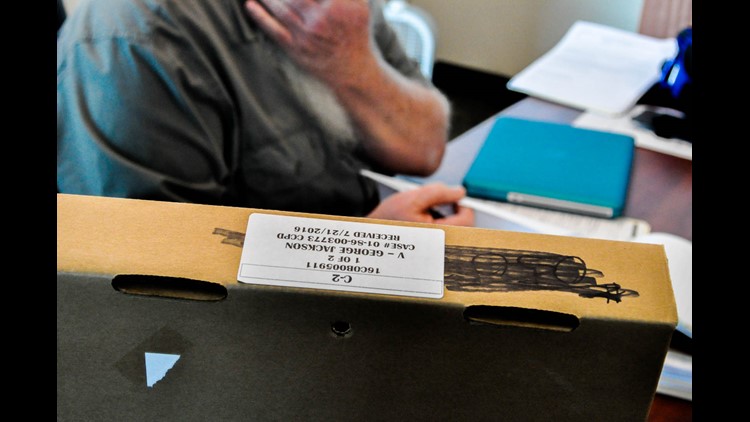

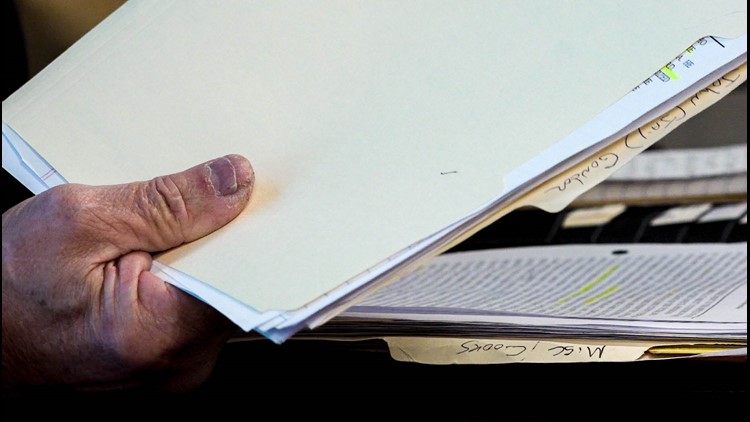

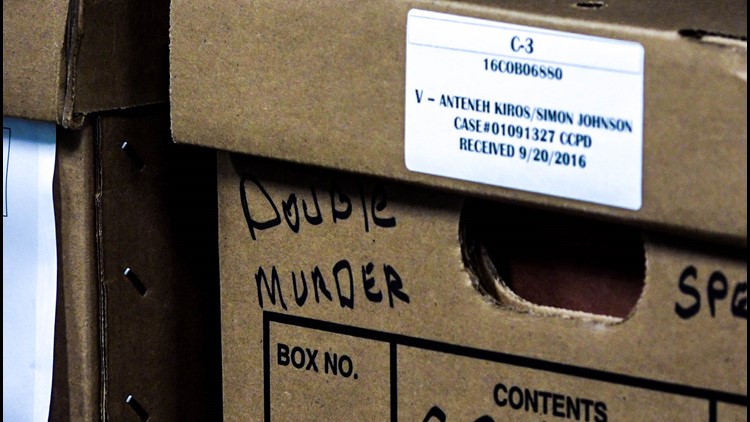

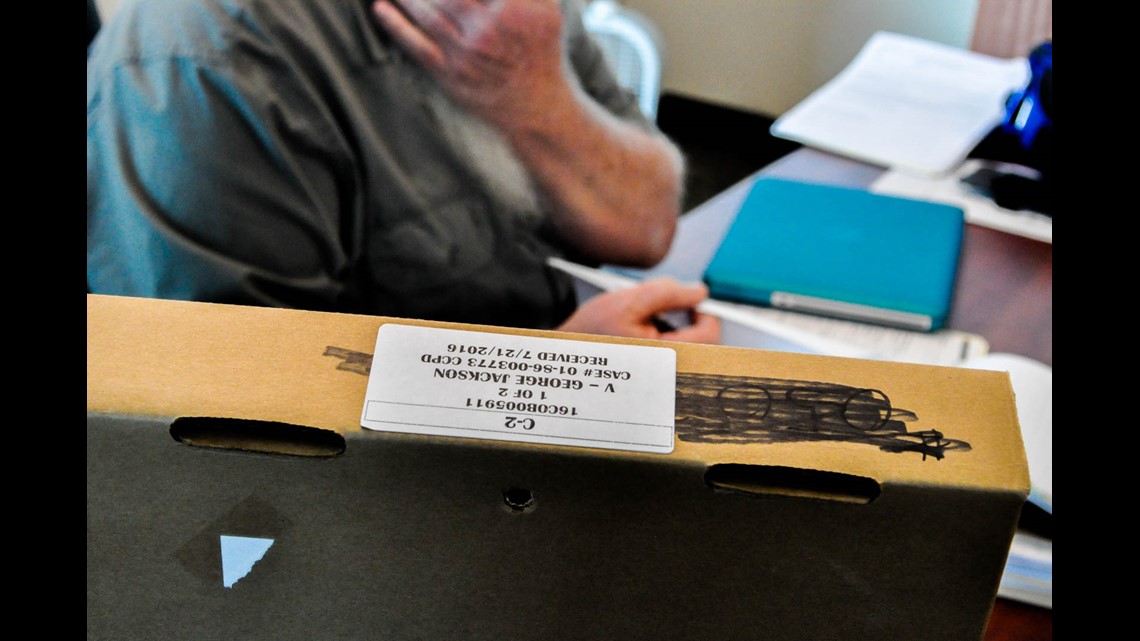

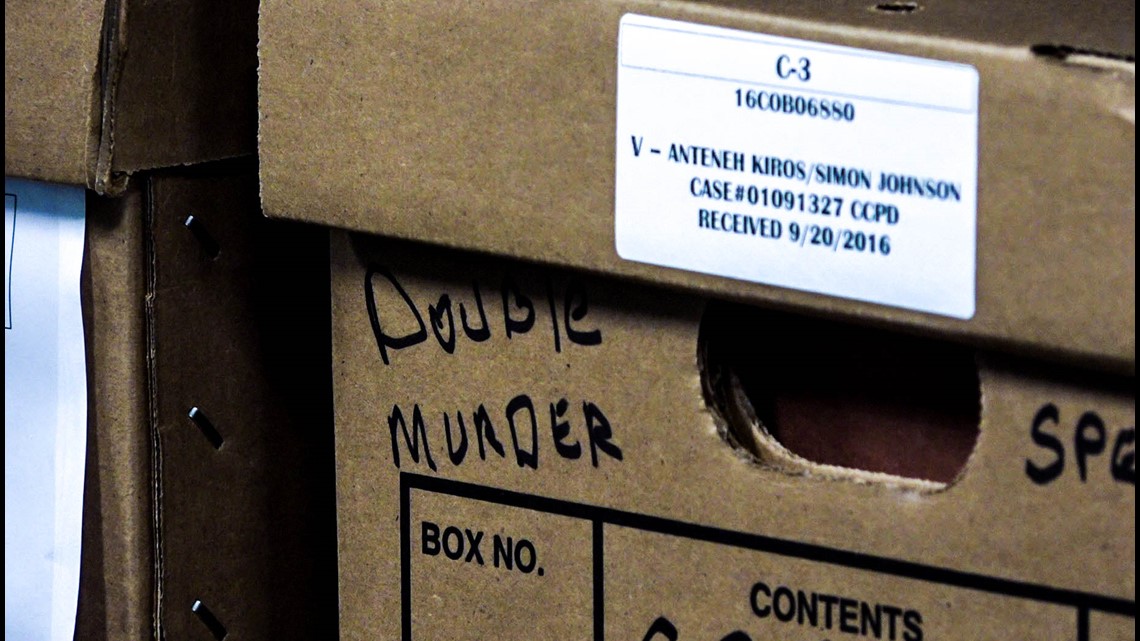

Each tan cardboard box is labeled with a case number, the crime and a last name. But inside, the folders clutch victims, families and their tragedies. They envelope stories of the unimaginable, the wicked and unexplainable acts of horrific measure.

It’s those stories that keep the veteran detectives chomping at the bit.

Dawes was hired by the Cobb County Police Department in October 1985.

But, the officer spent very little time in uniform.

“I wanted to get into the investigative side of the police department,” he said.

And, so in the late ’80s through the early ’90s, Dawes investigated crime scenes, specifically burglaries.

In 1992, he transferred into the homicide unit and worked there until 1997, when he moved over to the DA's office as a criminal investigator, putting case files together pre-trial.

Six years later, he shifted to the medical examiner's office and worked as a forensic investigator.

In 2003, Dawes admitted that he missed the chase, so he returned to the police department and finished his last 10 years on the job within his beloved homicide unit.

“Most of my career, 29 years with the police department, ended up in major felony crime investigation. That's where I always wanted to be and that worked out well.”

After, what he believed to be his final decade on the job, Dawes retired on Dec. 1, 2013.

But that wouldn’t last.

PHOTOS | Charlie 4: Cold but not forgotten

Opening a unit, closing cases

When Reynolds took office in 2013, an idea sparked.

“[Vic] approached me late in 2013, just before I was going to retire from the Cobb County Police Department, and asked me if I would consider heading it up,” Dawes said.

“It was very flattering. I've known Vic for a long time. He prosecuted my first murder case in 1992.”

When Reynolds first came into office he found that there were about a hundred unsolved cases in the county.

It was numbers like those, that didn’t sit well with the newly elected DA.

“I was very surprised at that number and began a process of deciding or thinking of how we could go about solving those crimes and bringing some closure to victims’ families. And so, that began the genesis, or that was the seed that was planted to start the Cold Case Unit,” he said.

“I think anytime a crime occurs and there’s an actual victim and that family is left to try to resolve the issues that come with being a victim or a victim’s family, that healing process can never really begin until that crime is solved. Until the victim or the victim’s family knows, this is who did this to me or to my loved one.”

Two years after taking office, Reynolds decided that to convict as many criminals in his county as possible, something fresh would have to be created.

Reynolds officially gave Dawes the nod and go-ahead in February 2014. And that’s how the Cobb County Cold Case Unit got its start.

Not including the nearly 100 unsolved homicide cases in the cold case unit currently, there are about an additional 75 murder cases throughout the county that are unsolved within the police departments' own cold case units. As well as more than 400 unresolved rape cases.

“In the case of cold case homicides, obviously, the victim is no longer with us. He or she is deceased. And therefore, that family left with not only this tremendous sense of grief—and they’ve lost a loved one—if you multiply that with this tremendous burden of not knowing who did that, what happened to their loved one,” Reynolds said.

“That really, is what motivated this office to say, ‘We need to solve those; we need to really, begin taking a hard look at some cold cases, so we can begin that process of healing and closure for a victim’s family.’”

And for Reynolds, Dawes was the perfect fit to lead the unit.

“John’s the kind of guy, he’s focused; he has a great deal of tunnel vision. Once he locks on to something, he is a proverbial bloodhound. And that’s the kind of guy you want working homicides."

“Probably one of his strongest traits is that he goes into a case open-minded; he doesn’t go into it with some indication that ‘I’m going this way’ or ‘I’m going that way.’ He lets the evidence take him where he needs to go, and that’s what good investigators do. And we are really, very fortunate to have him administrating and running this unit. He sets the guidelines, the principals, the vision.”

Getting off the ground wasn’t an easy task. They had some budgetary issues, as do most governmental agencies, Reynolds recognized.

Challenge accepted.

They reached out to the Fraternal Order of Police (FOP) Lodge and revealed their ambitious plan for a new cold case unit, and soon, eager volunteers started coming out of the woodwork.

“It got to the point where we were fortunate enough that we could actually weed through and filter through the folks who wanted to volunteer with the unit,” Reynolds said.

From the several enthusiastic, retired detectives, Dawes handpicked eight detectives with prior homicide, military and gang experience to work in the unit.

Now, in his third decade of law enforcement, Dawes is solving cases as old as, or older than, his career.

And he wouldn't have it any other way.

“To me, homicide investigation is all the energy. It's the most heinous crime on the books in the state of Georgia. It affects not only the victim, but it affects their family."

“We're all supposed to, under the norm, live to the ripe old age of mid-70s; watch the 11 o'clock news; go to bed and not wake up—just die a natural death very peacefully. But there's a certain percentage of our society, based on greed or selfishness or whatever emotion, make a difference in that, and they resort to violence to satisfy what their wants and wishes are,” Dawes said.

The “hot portion” of the case, Dawes said, is within the first 48 hours.

“You have the emotion. You have victimology to do. You have a lot of different things to do in the first hours of a case. And many times, that's when a case does break, within those first 48 hours, because even the bad guy, most of them, have some conscience, and they exhibit that through their behavior and you can get onto a suspect—and if you have the [evidence], you can make the arrest,” Dawes said.

But once that case goes past 48 hours, it gets more and more difficult to solve the case each day.

“It still goes back to the old school knocking on doors and beating the bushes, and finding answers.”

So, how is this unit different?

Most cold case units that you hear about are embedded within one police agency, Dawes explained.

The Atlanta Police Department has a cold case unit and they are Atlanta Police still working for Atlanta Police and they only look at Atlanta Police cases, he said.

In the Cobb County unit, the difference is, they work with seven different police agencies under the umbrella of the DA's office.

The unit is available to help any law enforcement agency within Cobb County, including Acworth, Austell, Kennesaw, Marietta, Powder Springs, Smyrna and Cobb County Police, that has murder or sexual assault cold cases.

“I think that from the inception, Vic had an incredible idea,” said Dawes, who has a tough, weathered exterior, indicating years of hunting down criminals and a dogged persistence to see that justice is served.

Now, he seeks answers for any department in the county who might need a renewed look into a case they’re working.

“The police agencies of today are overwhelmed with current crime. There's really not the manpower or the time to go back and look at these old cases, because you pull one of the shelf and your phone rings and you're on your way out the door to the next case that just happened.

“We're not waiting on the phone to ring; we're not expecting the phone to ring; we're not going out on something hot and current. And, any of seven police departments inside this county can call us up and say, ‘Hey, we've got this... can you look at it?’ And we're gonna hop all over it and be glad to do it,” he said.

‘It's a calling’

“I've kind of formed and assembled a team in a purposed strategy—and that is, that no murder case is the same as the next; they all have different aspects to them,” Dawes said of his unit.

For instance, there are a lot of drug murders, and so, he said, he brought in a guy who started the Marietta-Cobb-Smyrna Narcotics Task Force in 1980 and spent 25 years “working dope.”

“He's brilliant in the drug industry and he understands how these suppliers work, how drugs work, how they get into these groups and form their organizations, and he is absolutely full of energy to continue working,” Dawes revealed.

The unit has an expert in crime scene investigation, as well as an expert in statements.

With those different layers of expertise, the unit has a about 270 years of combined experience.

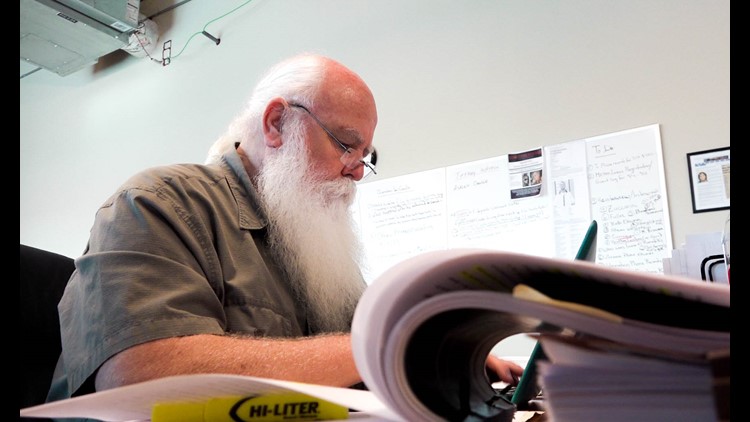

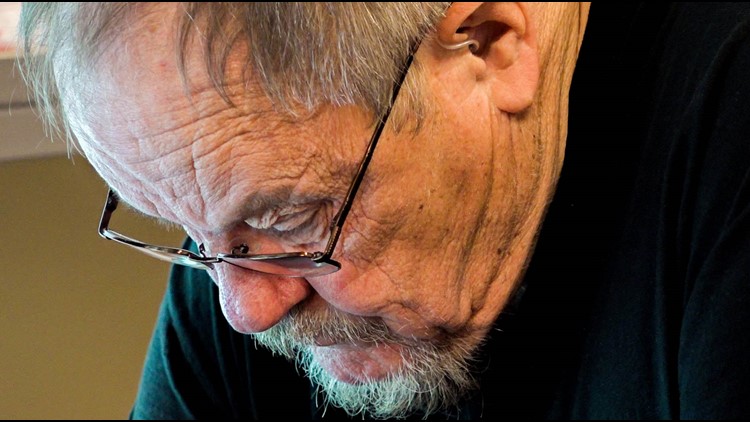

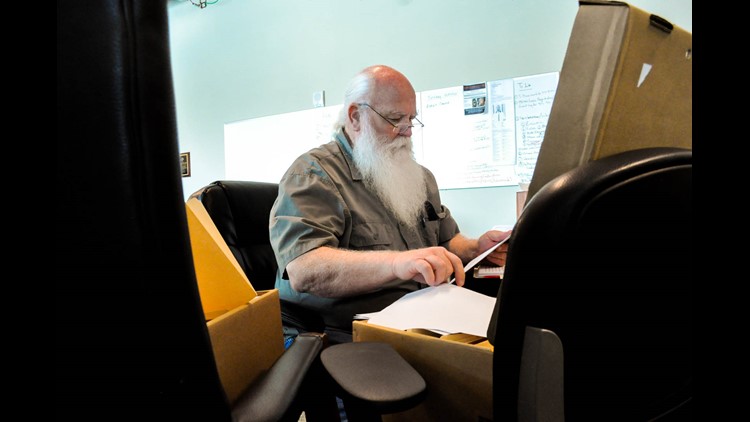

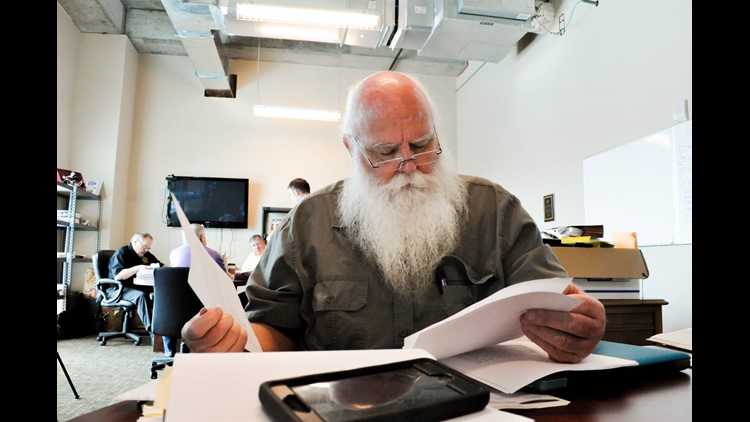

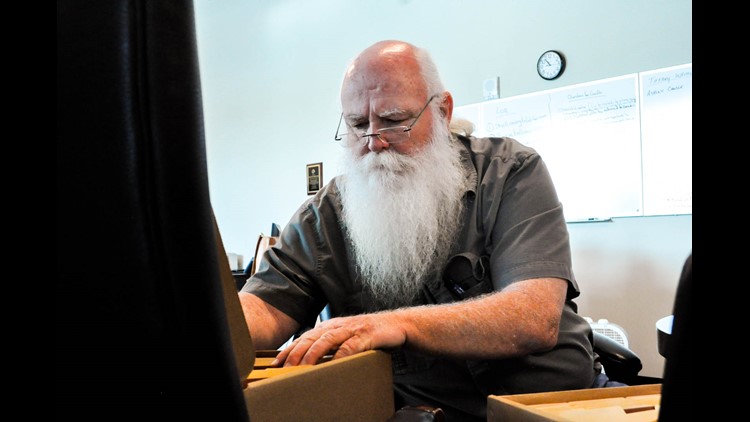

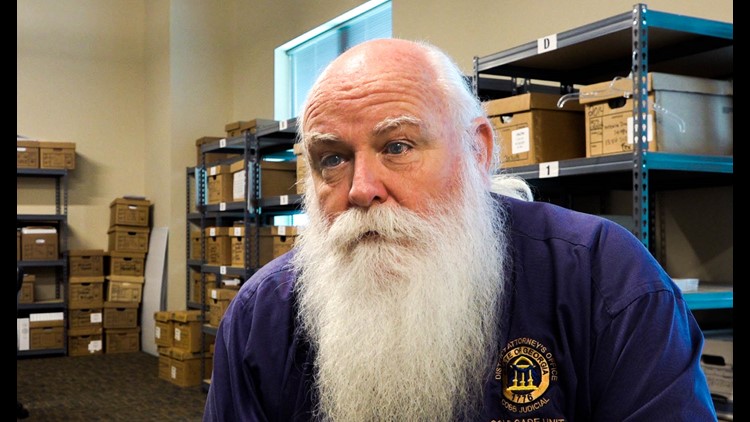

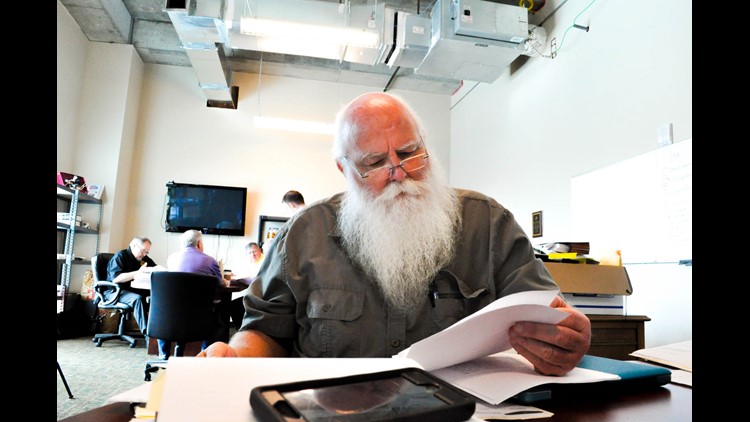

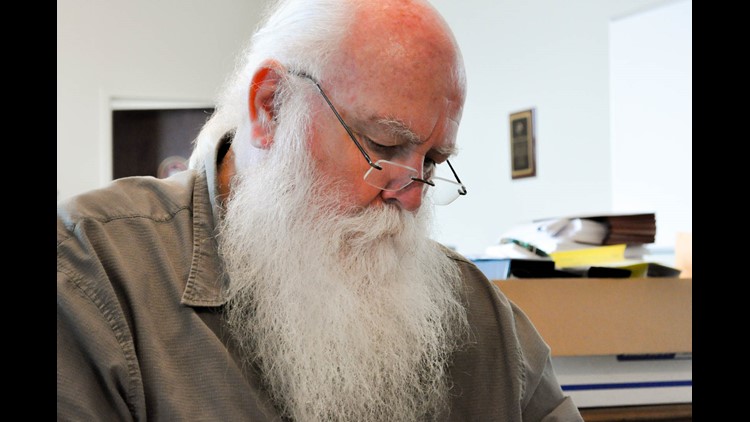

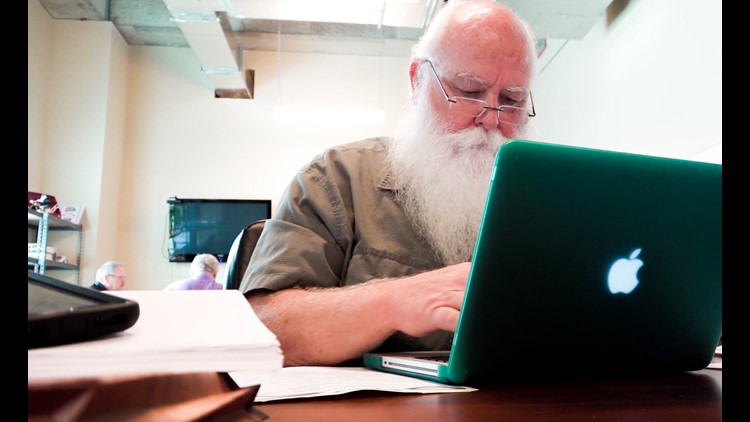

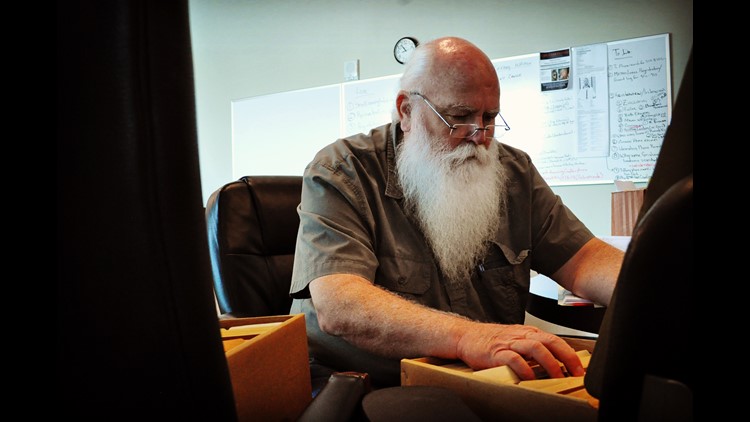

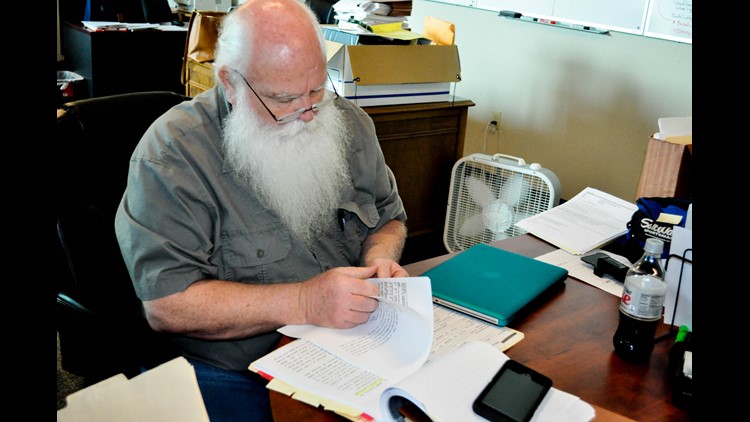

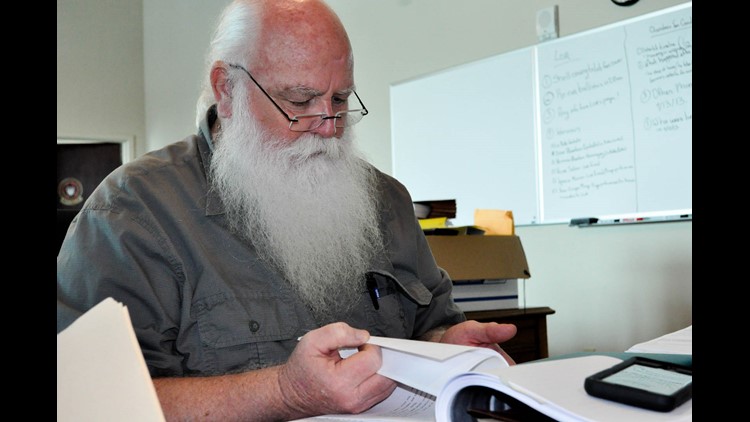

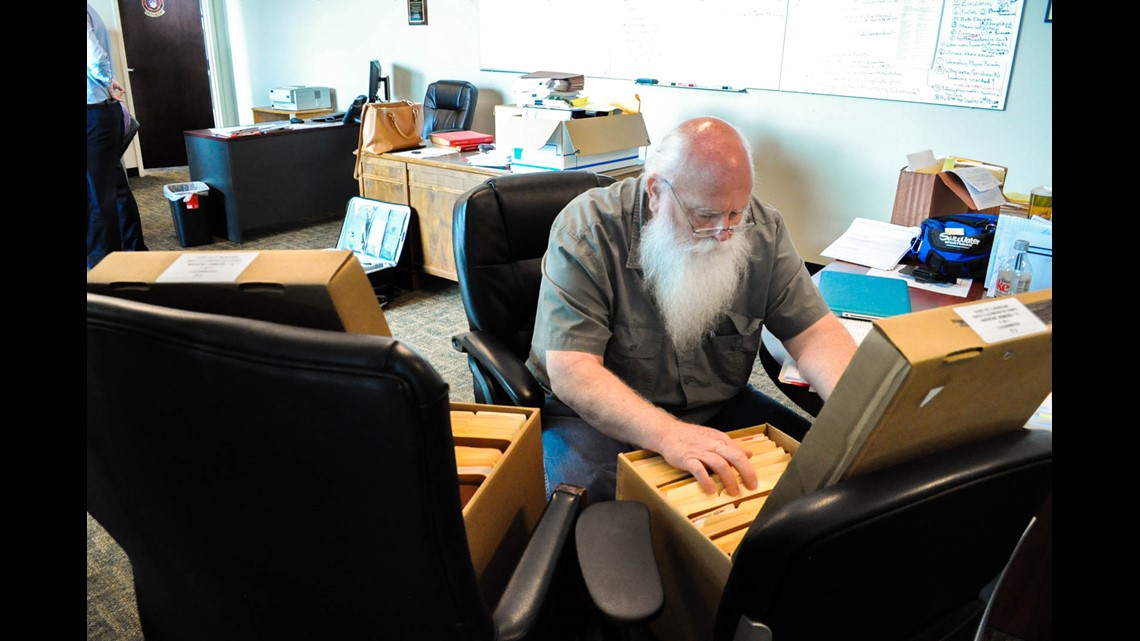

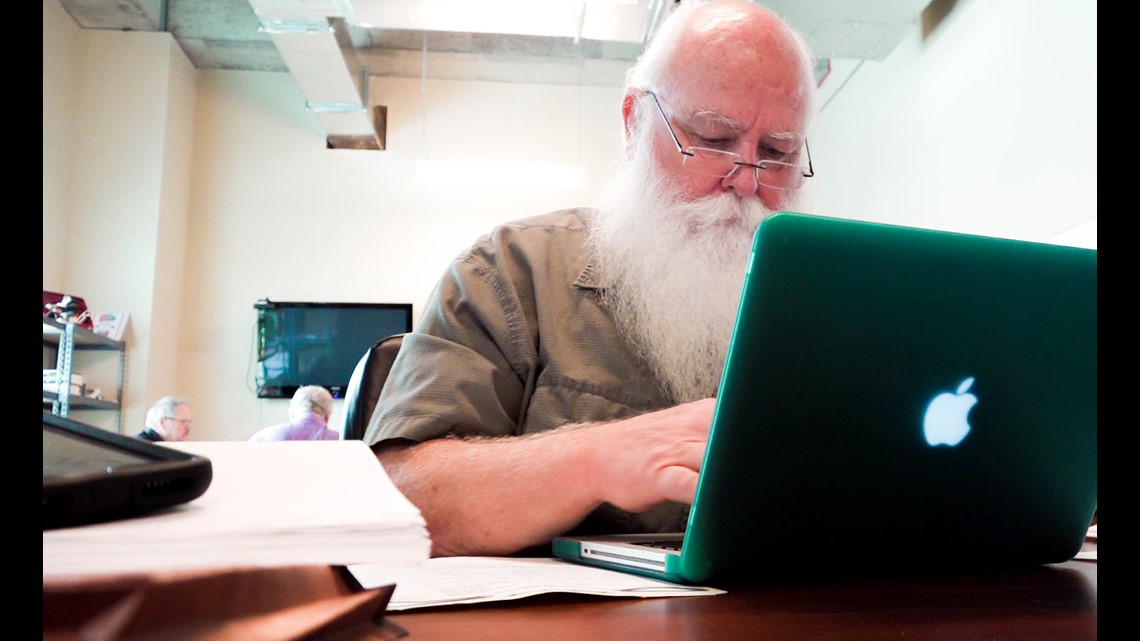

John Thompson’s long, fluffy, white beard sweeps his chest and he peers just over his clear-framed reading glasses, resting on his wrinkled nose, to read his Macbook’s screen. It's no surprise he's also been a part-time Santa Claus for more than a decade.

The 62-year-old is a retired Cobb County homicide detective and now, one of the volunteer detectives with the Cobb County Cold Case Unit.

“I'm not a typical, hard detective. I try to have humor, because as a detective, we see the worst that mankind offers man. You see the worst that a spouse gives to another spouse when they claim that they love them, but yet, they beat them to a pulp and kill them.”

And in this job, he said, “You're not always there to see the best of what mankind can do. You see the worst.”

His career began while he was enlisted in the Air Force, as a K-9 unit in the jungles of the Philippines and narcotics work in Korea.

In 1981, he made his way back to his hometown county, Cobb County and joined the police department—first as a uniform patrol officer, then a tour on motorcycle duty.

But after an accident that injured his back, he patrolled on the midnight shift.

Eventually, he made it to a detective role, starting out in the burglary unit in East Marietta’s Precinct 4—until he was transferred to the new precinct in Kennesaw and began his work solving homicides.

“The key thing is, on the murder, your victim can't tell you anything verbally. There's physical evidence at the scene and that tells you a lot,” he said.

And now, he relies on years-old evidence to solve the crime.

In January 2014, following his Santa shtick, Thompson joined the unit as a new set of eyes on unsolved homicide investigations.

“The difference between active duty cop and what we do here in this cold case unit, is we're taking cases that have pretty much run their course, but they're still not solved. We go back over these cases; we go through and read pages and pages and pages of reports. Sometimes we catch things that are missed by the active investigation.

“Sometimes we can catch the little tale that's in there that the bad guy gives us—the little slip-up may have been glossed over.”

Being a part of the volunteer team, he said, is a new opportunity to do what he loves, bringing with him years of experience and a certain skill set that others may not have yet.

“Yeah sure, in the active duty police department, we're the old guys... and, 'Why don't you all just go to pasture or something. You're old. You're old. This is a young man's game.'

And, he agrees. As he has aged, he can't run an 18-year-old kid down on foot anymore. He can't fight and wrestle with the perp to get him handcuffed.

“But, I have learned things and can do things, mentally, that some of these younger guys have never done or seen before. So, there's a vast amount of knowledge in the older people that [got] wasted until this unit.”

It’s a calling he cannot deny.

“It's the dedication that we have, the desire to use what we've trained with, and to put a bad guy in jail... a bad person, a criminal—put him in jail, lock him down where they belong. So, they can't hurt anybody else.”

“Once you get involved in hunting killers, armed robbers, rapists, aggravated assault—once you get into that, it's just a good feeling that you caught the guy, or the gal, and you built the case and you got the evidence to lock them up and put them away.”

He quotes Ernest Hemingway: “There is nothing like the hunting of man, and those who have hunted armed men long enough and like it, never care for anything else thereafter.”

“It's a dedication; it's a desire; it's a calling. And I just keep doing what I can do.”

“There's probably nothing greater than to look at the family at the end of the trial, when the bad guy is convicted and sent away, and the gratitude that you see in their face—the hug they give you for sticking with it.”

Proudly donning a Cobb County Cold Case Unit polo shirt, he points to the stacks of shelved boxes.

“Each one of those represents a challenge. Each one of those, when I look at that, it tells me that we're not done. We have more work to do… they’re not forgotten.”

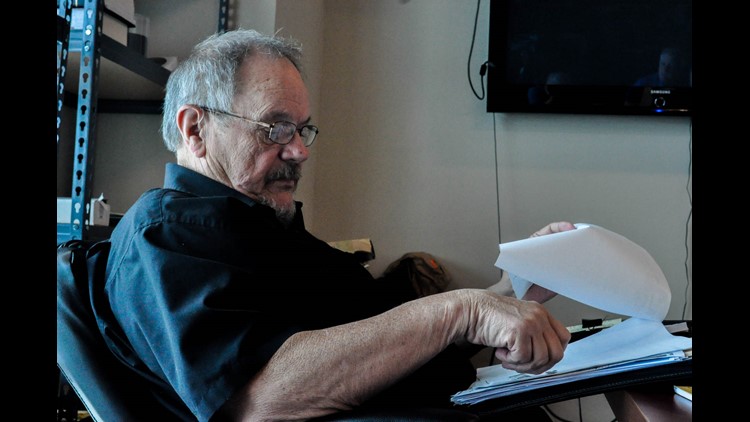

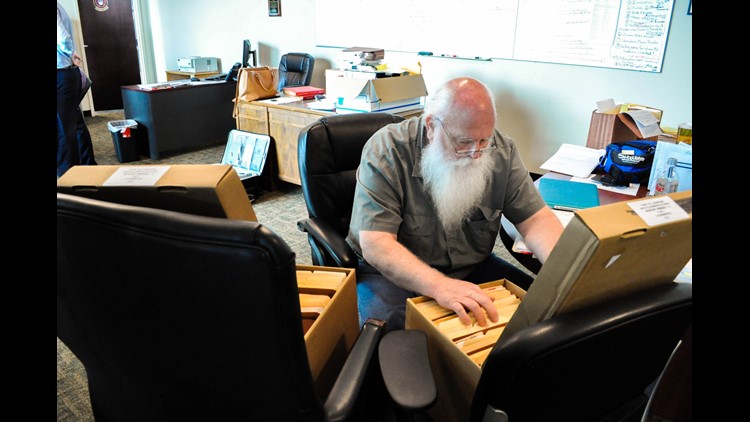

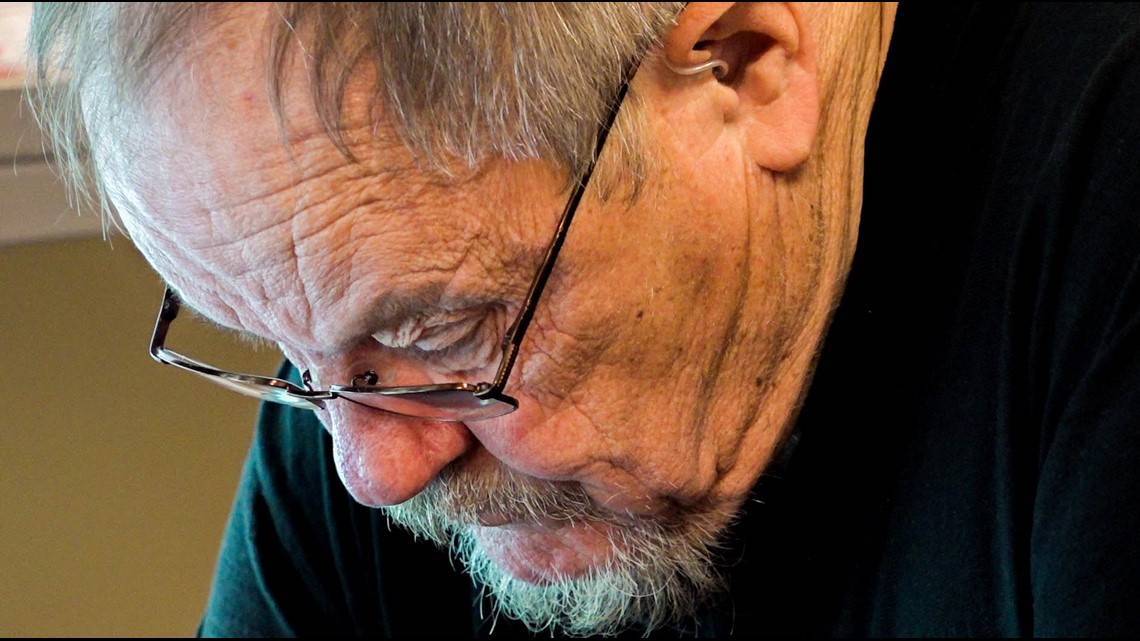

A gray-haired Jimmy Maxwell rifles through file boxes, looking through evidence and paperwork—his fingers, deep with wrinkles, peel open each folder, searching for the clue that has been overlooked, and getting to know his victim.

All the cases stick with him. And every box has a story inside. It's his job to unlock and uncover the story within, to reveal the ending, establishing answers.

“Every box here has got a personality locked up in it. It's got a background locked up in it. It's got a person's family; it's got their past, what they did. And when you open it up, you get to know these people,” Maxwell said.

“You have to look at it and say, ‘OK, first of all, who did this to you?

‘Why were you in a situation where somebody would hurt you?

‘What was you doing?

‘Was you doing something wrong?

‘Was you selling drugs?

‘Was you a prostitute?

‘Did you make somebody mad?

‘Was somebody jealous?’"

They could be associated with a hundred-different people, he said. So, he makes it a priority to get to know each box’s story.

It's the connection to the case, that keen sense of hunting down leads, and digging deep into the investigation that keeps him motivated these days.

“It's not out of my system... that's why I'm here. I've done it for so long, it's been a part of my life for so long,” said Maxwell, who retired from law enforcement in 2000.

His specialty: drugs.

He served the Cobb County Sheriff's Department for 27 years, beginning in the early ’70s and had several undercover assignments over the years.

In 1980, the now-73-year-old was one of those instrumental for spearheading a multi-agency narcotics operation, with 35 agents in Cobb County. He was the commander for two decades.

The war on drugs was on, he said.

That war helped his fight against dealers. It allowed him to get into their heads.

“I understand the workings of some of these drug dealers better than somebody that's working drugs nowadays.”

There are several variables that you must identify to get to the answers you need to solve the case. And not only does he have the investigative skills, but the knowledge of the drug trade.

“I have a lot of experience in dealing with drug violators and drug investigations,” he said. "I probably know more about them than they did themselves when they were alive."

The biggest culprit in drugs is greed.

“If somebody knows you've got money or just made money on a big drug deal, that means they'll take it. And taking your life doesn't mean nothing to them.”

Whether they're a drug dealer, a trafficker, or a user, he said, when it comes to life, there is no rank.

“Even the lowest person working on selling drugs on the street or the highest person living in the high-rise down here selling drugs, I don't show any difference in the way I feel about them. They're all human beings and all had a right to be here, and somebody took their life and didn't have the right to do it.”

In 2015, Dawes called Maxwell in to work on a double homicide from 1980, that involved drugs.

“I guess the bug bit me,” he said with a chuckle, straightening his silver-framed spectacles.

“When he brought me back, it was like giving me a shot of adrenaline. I was ready to rock-n-roll then.”

And he has a message for suspects who have eluded the law for years.

“I'd like to keep the pressure on and let people know, that if they did something around here, that they've got a bunch of people in here that's hot after them… We ain't gonna cut no slack,” he promised.

PHOTOS | Solved: Charlie 4

Unlocking the key to solving crimes

DNA has been a fundamental tool for the Cobb County Cold Case Unit to close cases and put criminals away in the 21st century—and, sometimes, is the only voice for the victim.

“Many of these cases that we have in unit, because of their age, weren't able to be solved because technology wasn't there and now DNA is moving forward every day, and we're able to solve cases just with that evidence sometimes,” Dawes said.

The hiccup, however, was the price tag.

The cost for a DNA test is, on average, about $1,100. And each case consists of about 10 pieces of evidence, running the unit about $11,000.

But in 2014, the unit was awarded a $250,000 grant from the U.S. Department of Justice, specifically for the purpose of testing of forensic evidence.

With the grant’s funding, the unit submitted over 100 pieces of evidences, involving approximately 35 cold cases… and hit pay dirt.

SOLVED: Justice, best served cold

Seven people have been charged following the Cold Case Unit’s assistance, including six murder suspects—many credited to new DNA matches through the Combined DNA Index System (CODIS), which stores all convicted felons’ DNA.

“Technology itself, science itself, lab machinery, lab personnel, the training and the technology has become so advanced—and then when you combine it with an index of convicted felons, we're able to get hits a lot more frequently than in the past,” Dawes said.

“So, if we're looking at a case from 25 years ago where you left your DNA, we are going to find you. It's going to hit in the computer system,” he assured.

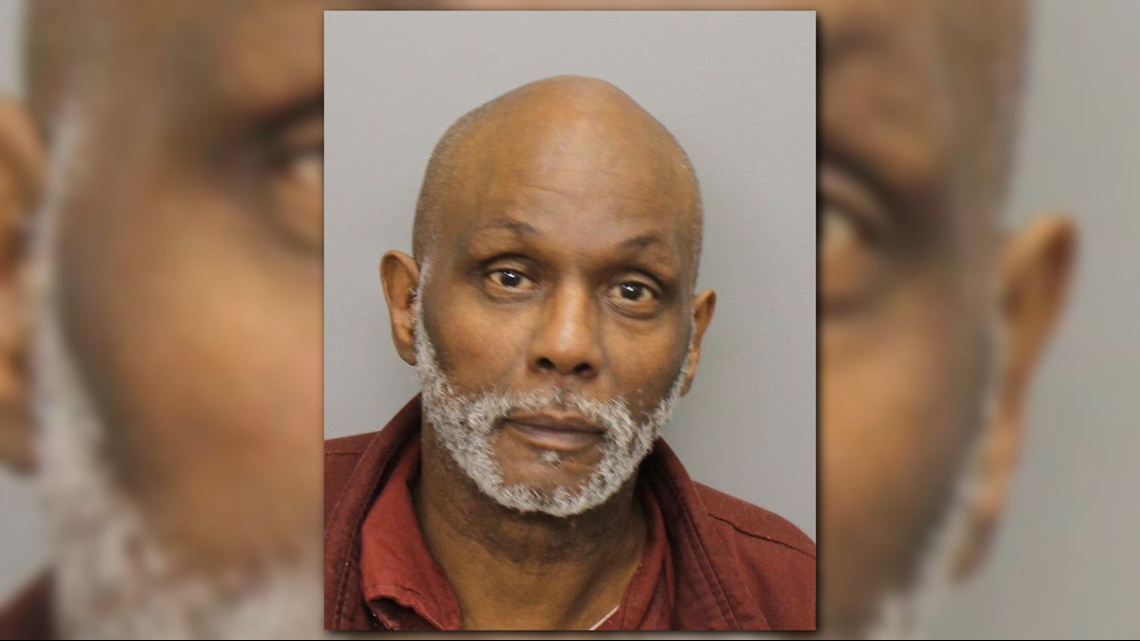

Ronald Lee Kyles is one of those alleged perpetrators who was caught.

He is currently awaiting trial for a double rape and murder from Sept.l 12, 1986.

In November 2015, Kyles was arrested for the rapes and murders of Sharon Brady and her 13-year-old daughter, Samantha, who were found dead in their apartment at 132 Cole St., in Marietta.

“Once we received that case in office, we went through the crime scene photos first and it was sickening. It was a case that we were driven to find some result,” Dawes remembered.

The unit reached out to the retired law enforcement officer who was the lead detective on the case back in 1986, and he came into the unit's office to discuss the case.

“It still bothered him. You could see it in his eyes—the frustration of the case to this day was... just frustrating beyond imagination. And we could identify with that because we were looking at the same thing he saw back on the day of the crime,” Dawes said.

Dawes and his team went to the crime lab and obtained 20 pieces of evidence that was still available, including blood samples and the original rape kits. He sent those samples to a lab in Utah.

Ten days later, they had a match.

“The DNA results were overwhelming—one in 1.3 trillion that it might have been somebody else... it was crazy exciting,” the cold case detective said.

At the time of his arrest, Kyles, now-62, was serving a 10-year sentence in Pennsylvania on an unrelated aggravated assault.

Dawes traveled to Pennsylvania, where the suspect was in prison for another stabbing. The Cobb County Cold Case Unit was able to extradite him, and hold him accountable for his decades-old crimes.

He was returned to Cobb County in May 2017 to stand trial.

“He looked at my jacket that said, ‘Cold Case Unit,’ and he knew,” Dawes said with a smile brimming with satisfaction. “They know when you come to see them from the Cold Case Unit that you found them.”

George Gengarelly, 63, committed suicide in Cobb County Jail before he was indicted, following his DNA’s CODIS match in a 1991 rape and murder.

The partially clothed body of 37-year-old Yvonne Weems, of Atlanta, was found off Lake Acworth Drive in Acworth. She had been sexually assaulted and shot to death.

Gengarelly, of Hernando, Fla., was charged with murder, aggravated assault, aggravated sodomy, rape and possession of a firearm during the commission of a felony.

Terrance Wright is serving life sentences in two other states, however, there is a warrant for his Cobb County charges related to a 1992 attempted rape and aggravated assault.

On the morning of Sept. 3, 1992, the 43-year-old victim was alone in the leasing office of Canterbury Lane Apartments at 152 Dodd St., when Wright allegedly walked in and inquired about renting an apartment.

Without warning, he pulled out a knife and forced the woman into the bathroom. But while he was taking off her shoes, slip and panties, he was interrupted by a noise. It startled him and subsequently stabbed the victim three times in her chest and fled the scene.

The victim survived her injuries.

In January 2016, Cobb Sheriff’s Office tested forensic evidence in the case using procedures not available in 1992, and received a match to Wright.

Wright, now-48, is serving a life sentence for murder in North Carolina. He was also convicted of rape and murder in South Carolina, according to the DA’s office.

“When terrible crimes fade from the headlines, surviving victims and loved ones are left suffering in silence from emotional scars, sadness and apathy resulting from the crime,” Marietta Police Chief Dan Flynn said in 2016 after Wright was charged. “Meanwhile, the cold case unit, which exists for the sole purpose of giving a measure of closure and justice to the victims and indirect survivors, does not forget.

“The law has long arms, and truly, it is gratifying for the law enforcement community to be able to render justice, especially when others have given up on it.”

James Lorenzo Randolph was convicted of Rodney Castlin’s 2000 murder in April 2016.

In October 2014, Cobb County Police charged Randolph, then-34, and U.S. Marshals arrested him in Richland County, S.C.

Randolph was convicted of killing the Kennesaw hotel manager, father and husband during an armed robbery on Dec. 7, 2000, and was sentenced to three consecutive life sentences, plus 35 years.

Joshua Moulder is awaiting trial for a 2006 murder in Smyrna.

Moulder was arrested in 2014, then-35, in Xenia, Ohio for the murder of 41-year-old Anthony Tyrone Rudolph, of Cleveland, Ohio. Rudolph was found shot to death on July 22, 2006, at the Knights Inn, located at 5230 South Cobb Dr., in Smyrna, Ga.

Sharon Poss is awaiting trial for the April 2013 murder of her husband in Kennesaw.

The 57-year-old Poss was arrested in Cartersville, Ga., for killing 52-year-old Frank William Davidson, who was found dead at the 3500 block of Paul Samuel Road.

In 2016, Poss was arrested and charged with felony murder and aggravated assault with intent to murder.

Joshua Gibson is awaiting trial for the 2013 murder of his baby’s mother.

In the early morning of Jan. 14, 2013, Danielle Marshall, 23, was found dead in her home on Palomino Drive. Her baby was also home, but uninjured.

The infant’s father, Gibson, called police. He claimed that when he arrived at the house, Marshall was not answering the door and he could hear the baby crying inside.

But police believed he was responsible for her murder.

In 2015, Powder Springs Police arrested Gibson, 27, and charged him with murder, aggravated assault and possession of a firearm during commission of a crime. It was the only homicide in the city for 2013, according to then-Police Chief John Robison.

“It is a relief to me that it appears solved,” he said shortly after Gibson's arrest. “Nothing will ever bring back that child’s mother, but we look forward to justice being served.”

It’s another case closed for the unit.

“Our mission in here is that once we get a case, it doesn't get dusty again. We're not going to give up on it. If we find a dead end, we're going to go around it. We don't believe in road blocks. We believe in doors and windows,” Dawes said.

“When you get to that point and you can reach out to the family of this deceased person and say, 'Hey, we got it.'"

The second-most gratifying moment, he said, is when he sits down across the table from a criminal, and you know you got him.

"When you start talking to him and you see their facial expression change and you see the look in their eye change, you see their head drop, and you know you got him--there comes a point when you can see it in their face. They're full of guilt. They're full of emotions. They're full of ‘What do I do now?’ And that's an incredible feeling when you know that they have experienced, ‘I've been caught,’” Dawes said.

Some cases, however, continue to stump even the most meticulous and dogged detectives.

A family massacred, a case left cold

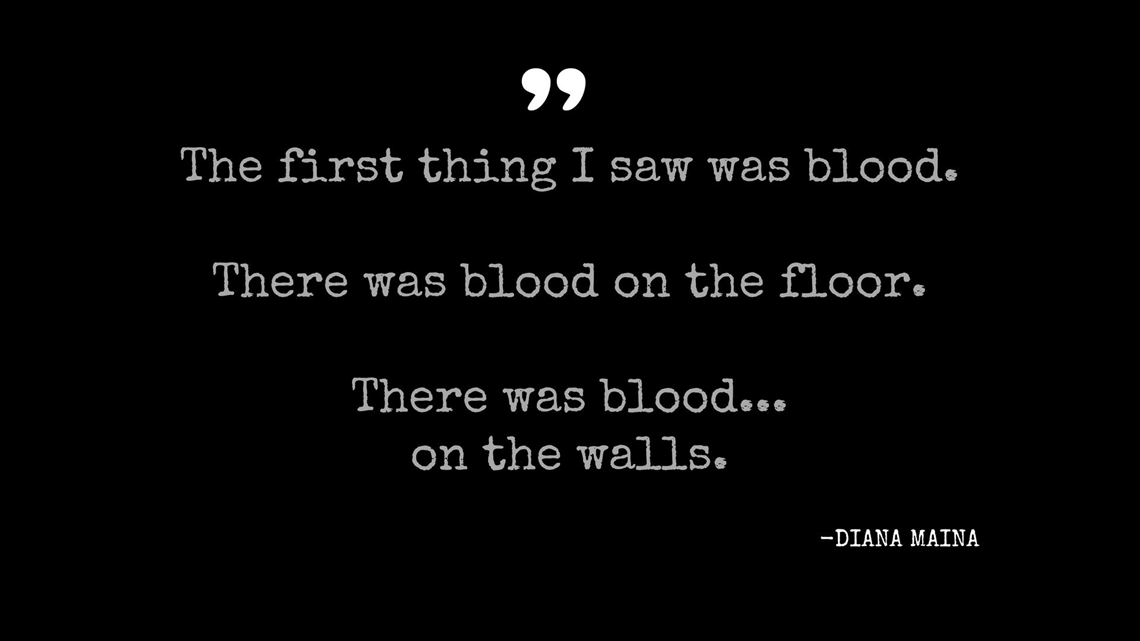

Diana Maina slid the back door open and crept inside her aunt’s Powder Springs, Ga., tan and white suburban home.

The shades were drawn, keeping the hot, summer sun at bay, as cartoons whimsically played on the T.V., illuminating the room—revealing the gruesome acts that had unfolded days earlier.

Standing in the doorway of the kitchen, paralyzed with fear, the only thing she could see was blood.

“There was blood, like, on the walls, and it was really, really dark,” her big brown eyes growing wide as she recounts what she stumbled upon.

And bodies.

There were bodies everywhere she turned her gaze.

It was a massacre.

It was Wednesday, Aug. 1, 2007.

Maina, then-21, was asleep when her aunt, Pauline Thande, woke her up at 9:30 a.m., in a panic. She had been trying to get ahold of Maina’s other aunt, Jane Kuria, without success. Her cousin, 11-year-old Peter "PK" Thande, had been staying with the family of four after arriving from Kenya.

Her other cousin, Owen Thande, who was living next door to Maina, had been to the house the day before to check on him, she recalled.

He told her that he looked through the side windows attached to the front door, but he couldn't see anyone or hear anything. He didn’t see any signs of struggle or disarray.

Since he witnessed Jane’s black Toyota Corolla in the driveway in front of the two-car garage, she said, he just figured that someone picked the family up for dinner.

So, he left without any further investigation.

But by Wednesday morning, no one was answering the door or the phone.

*******

Maina, with her Aunt Pauline in tow, drives the 15 minutes to Kuria’s house, at 4789 Country Cove Way—which she shares with her two daughters, Isabela, 16, and Anabelle, 19, and her 8-year-old son, Jeremy.

They pull up to curb alongside the unpretentious white house and park on the suburban street. The sun peeks through the clouds, burning the dew from the manicured lawn.

Her aunt is in complete panic mode, talking a million miles a minute, shuffling up to the house.

“We get out of the car and she's was worried. [My aunt] was like, ‘Yeah, I don't know what's going on... it's so unlike her. You know, I have my child over there. I don't know. I haven't spoken to him.’”

PK hadn't spent time with his mom since arriving to the United States from Kenya just days earlier, and she’s anxious to see him—and assumes she will once they knock on the door.

Maina advises her aunt to climb the white steps leading to the green front door; meanwhile, she will check the back door to see if anyone answers there.

She thinks to herself, “It's almost 10 a.m., someone should be up making breakfast by now.”

Instead of knocking on the front door, Maina's aunt follows her to the back of the house. They check the back door and windows, framed with green shutters, on the ground floor, but cannot see anything or anyone.

So, together, they hike the stairs to the split-level home’s second-story white deck.

The sliding door is adorned with long, white, vertical blinds—closed except for about a foot they can peek through.

Maina quickly realizes that the sliding door is unlocked and enters the kitchen, calling out for her aunt to step inside with her.

“I didn't know what I was calling her up for... I figured, ‘Everybody's up, so I'll just walk in.’”

But she does not find her family making breakfast.

She sees blood, and lots of it. She immediately warns her aunt to stay back.

“When I saw blood, I told her, ‘OK, you cannot go in. We cannot go in; let's go back out. We'll call the cops.’”

Her aunt pleads with her to tell her what she sees.

She tells her, “I saw a body. I [don’t] know whose it is.”

She thinks that the lifeless, blood-soaked body closest to her is her Aunt Jane because she was face up, but she cannot clearly make out her face because of the severe swelling.

The two bolt down the stairs, when her Aunt Pauline begins wailing, begging for answers from Maina—asking her what she saw, who she saw, where, why?

The young niece reiterates that she only saw blood.

Maina grabs her phone to call 911, but she doesn’t know the address for the dispatcher, so, she darts to the mailbox, where she quickly finds a leaflet with their location on it to recite to the other end of the line.

In a steady voice, the dispatcher asks her what she saw.

“I saw a body on the floor and there's blood,” she relays to the operator.

Without hesitation, the Powder Spring Police, black unmarked cars and rescue crews begin flooding the scene and entering the house minutes later.

As a helicopter flies overhead, Maina catches a glimpse of an officer inside the door frame. He looks over to another officer and makes a gesture.

He holds up two, and then, three fingers—indicating how many people are inside the home—how many survived and how many died.

Maina sits inside a police cruiser as a veteran detective questions her, and finally, gives her some answers as well.

It is Dawes. He’s assisting the Powder Springs Police on the case.

He tells her two survived—noting that they had been unconscious for about 24 hours.

She immediately asks, “Who?”

“We need to know. We need to call everybody. We need to gather everybody. We need to call the family, because it's not just my aunt's son who's in there, all of these are cousins to us. We need let everybody know what's going on,” she said.

PK, who is found unconscious next to the couch in the living room, and Jeremy, who lay bleeding in his bed, are taken from the scene and swiftly transported to a nearby hospital—one by ambulance and the other by medical helicopter, in an effort to save their lives.

The detective tells Maina that all five were brutally beaten, but Jane, in the kitchen, Isabela, near the front door entrance, and Anabelle, who was in her bedroom, succumbed to their blunt-force traumatic injuries.

“Everything just kind of stood still and nothing moved. Everything is going on, but you're not making sense of anything,” she said.

“There was pain, anger—and more so, fear than anything else, because it's a whole family that are attacked and you wonder who else is next?

“Are they coming for us?

“Is it something random?

“That happening at that time, we thought, ‘They didn't even spare the children. Are they going to spare us?’ I don't know if I'm next or not. Really. Because you don't know what happened. You don't know what triggered it.”

That day, no one slept.

The family huddled together in a small room at the hospital. Everyone was trying to piece together their last moments, their last movements, the last thing that they were doing or the last time that they saw the Kuria family.

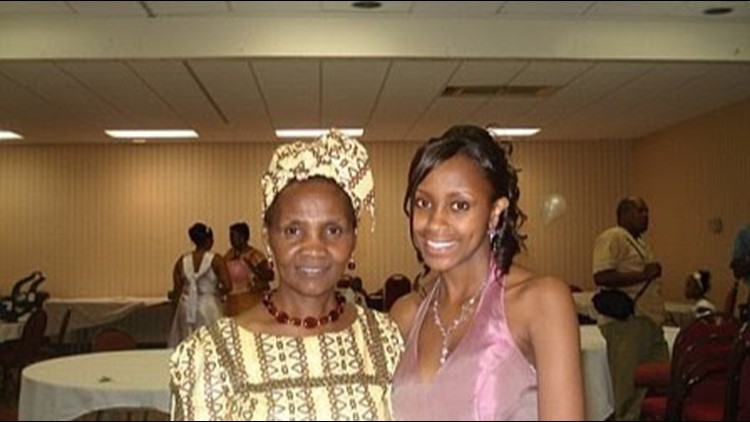

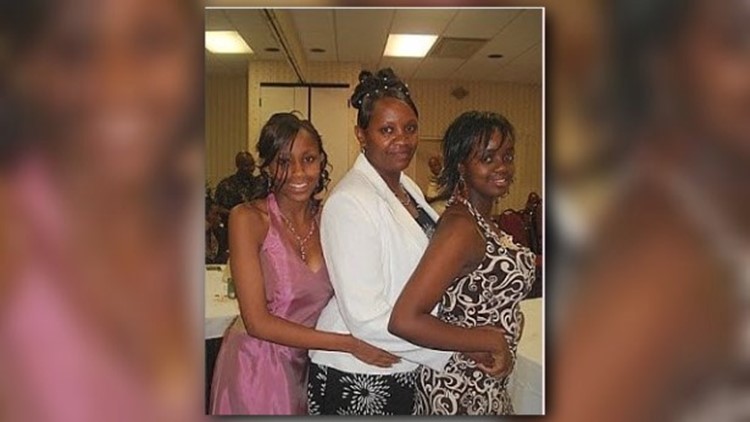

PHOTOS | Unsolved: Kuria family massacre

Jane, who moved to Georgia from Kenya with her children in 2002, was a single mother and widow.

“Jane was really, really hard working. She was so dedicated to her family. And even after her husband died, she was so dedicated to raising her children,” Maina, who moved to Georgia herself in 2004.

“We're very fun-loving people. We love people—so we wouldn't find any reason for that to happen, and especially to them, because they were so polite. And my aunt always got everyone together for, like, family dinners, get-togethers. She was just a beautiful, outgoing person.”

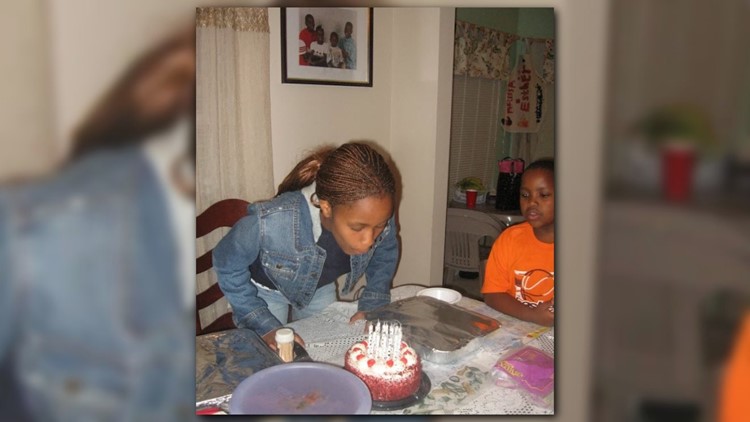

Isabela, who shared a birthday with Maina, was living in Chattanooga, Tenn., going to school to become a pharmacist, at the time of the attack.

Every year, growing up, Maina, who graduated from culinary school, said, the two would celebrate together.

“She was so polite… loved children,” she said.

By 2007, she said, they had grown out of sharing their birthday, but Maina still wanted to do something special for her cousin.

So, one day when she got off work, she ran to her neighborhood Walmart and bought her an India Arie CD and a card and dropped it off in her mailbox.

Maina sent Isabela a text message to let her know that she left her a surprise inside her mailbox. Her cousin text her back and said that, she too, had left her something in Maina’s mailbox.

Isabela got her an Amy Winehouse CD for her birthday.

The smiles, the laughter and the birthday parties are just a handful of memories that were seized the day that Maina’s aunt and cousins were slaughtered.

And the whole family, spanning multiple countries, craves the truth and justice.

“We've had my grandparents die and not ever know whatever happened to their grandchildren or their daughter,” Maina said.

“It's left us in a hopeless situation. You don't know how to go forward from it. Then again, you have to remember that we're in a foreign country, we don't know the right ways or the right channels—and especially then, because everybody had just moved here and was starting to get a new life.”

The two survivors of the massacre have moved on with their lives, but cannot help but look back at the crime that changed everything, knowing that their family’s killer is still out there somewhere.

It has taken Jeremy, now-18, time to heal—both physically and mentally, after losing his entire family to the unknown assailant. He recovered in the hospital for two months following the attack. But the mental scars have taken years to overcome.

“He's getting there. He's getting better,” Maina said of her cousin who is studying in Kenya to be a doctor.

He was asleep when the killer entered the home, doesn't remember much, she said, because he received a lot of blows to his head.

PK, now-21, has recalled memories from that day, Maina said. He remembers someone coming into the house, but not who.

Last year, according to Maina, while PK was eating ugali, a cornmeal dish with sautéed spinach, he looked at his mom and said that he remembered that, that was the meal they were eating the day of the attack. He also remembered the man who came to the house, and that he was wearing an African shirt.

Today, he is studying at the University of Nairobi.

“He is genius. He's a straight-A student; he's just a special child,” Maina, now-32, bragged about her cousin.

Now, she has her own family, including a 4-year-old daughter and a 2-year-old son, but the tragedy of losing her aunt and cousins a decade ago lingers in her heart.

“We still feel the loss in our family. Now, I have children; my cousins have kids. We'll always feel that loss, like, ‘Oh, my God, this is where they should have been. We should all be having fun together.’ So, we'll always, always feel that loss.”

And although many family members have moved forward with their lives, not a moment passes by that Maina doesn’t remember what she saw or what she felt that day.

“I think there's been lasting effects on everybody, not just the boys. I think it's for everybody. Knowing where the bodies were lying and how much blood was on the wall, knowing just what they went through, it's going to be damaging for everybody."

It’s an image she has never been able to erase from her memory.

“It sticks with you. Your really can never get it out of your head. It gets better with time... but still, sharp and clear.”

“Detectives said that they've never found... any kind of blood, that was not from the family,” Maina said. “There was just nothing. So, it's like somebody just came in and killed them and just left. But, how does that happen? And how is it that it's been 10 years and nobody has found anything?”

Maina still holds out for answers from Dawes—the detective on the case from the beginning, and again after it went cold.

“It's never been closed to us and don't think he's ever closed it. I just think he went from it being a case to a cold case,” Maina said.

It’s a case that has haunted Dawes.

“It’s one of the most violent crime scenes I’ve seen in my career,” he said. “In my mind, every day, I want answer on that case.”

That’s why Dawes has kept the case open for a decade.

“Having been in that initial investigation with Powder Springs, having the knowledge of the case facts, having relationships with the people that had been interviewed, to be able to get back in touch with them and say, ‘Hey, I'm still on it, in 2017, 10 years later,’ gives them a feeling that someone who knows the case is still looking at it."

“And it's a situation for me, where it's a good thing that I didn't just quit. I didn't just walk through cases for almost 30 years and then walk away. I'm still living those cases, I'm still able to work through those cases and see if I can find the answers now, years later,” Dawes said.

And his diligence to her family’s case has meant the world to Maina and the Kuria family.

“Nobody can really say how grateful we are. He has really been there, and he always answered our phone calls and questions. And anytime we have a concern, he'll always have us go to his office. I'm always going to be forever grateful for him. I am."

And she is confident that he will find who did this to them, and that he will make sure they get justice.

“He's very passionate about this particular case. I do believe he'll come to the bottom of it. I do,” she said.

“It's been 10 years, but we're still here. We still all love each other and care for each other, but I think we all feel the same way. It's about time it's closed, and we all got some closure.

If you have any information about a cold case in Cobb County, call the Cold Case Unit at (770) 528-3032.

For more of Georgia's cold cases, visit 11Alive's Cold Case page.

HOW WE DID THE STORY |

Gone Cold is an ongoing series, where 11Alive Journalist Jessica Noll investigates some of the most infamous and lesser-known cold cases in Georgia. She's digging for answers for the still-grieving families who long for them, and for the victims who have never found their justice.

11Alive Journalist Jessica Noll spent several days interviewing law enforcement and family to journalistically gather every aspect of the story possible. She investigated the cases, sifting through public records, court documents, police reports and photos.

This story is written in a narrative-style, long-form and was methodically reported in order to obtain each detail of the Castlin and Kuria cases.

CONTACT THE REPORTER |

Jessica Noll is a multimedia journalist, who focuses on in-depth, investigative crime/justice reports for 11Alive's digital platforms. Follow her on Twitter @JNJournalist and like her on Facebook to keep up with her latest work. If you have a tip or story idea, email her at jnoll@11Alive.com or call, text at (404) 664-3634.

Join our "Gone Cold" Facebook group and join our discussions about cases like these, at https://www.facebook.com/groups/gonecold/.