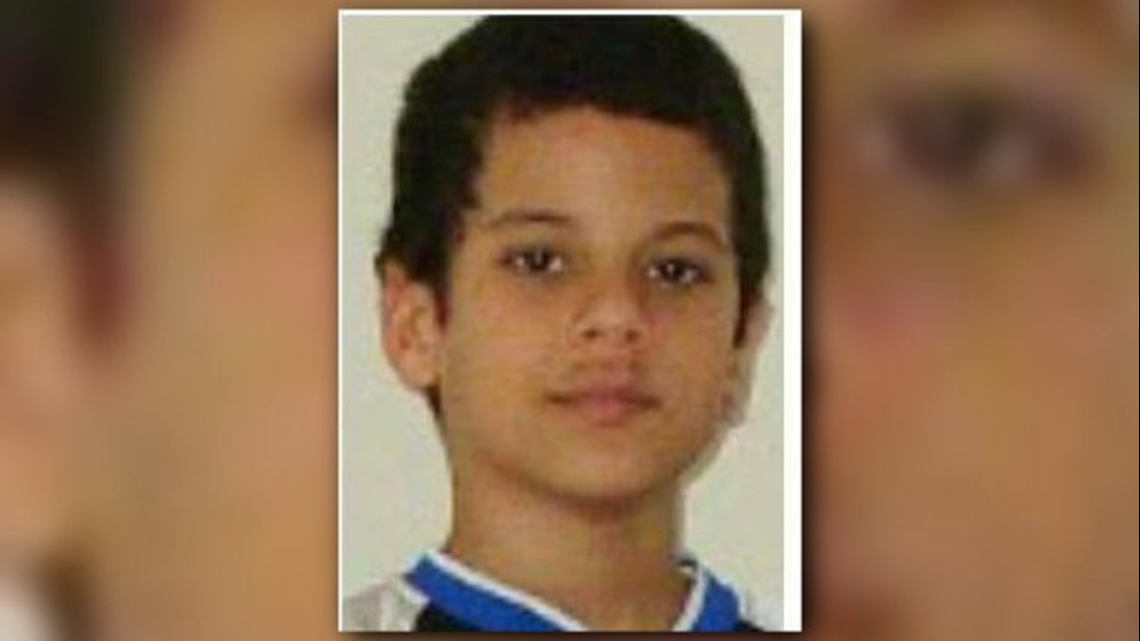

ATLANTA – Masika Bermudez’s 11-year-old son was named student of the month on April 16, 2010—that night he committed suicide.

In the past two months, more than a dozen kids have killed themselves in Georgia. And while the bulk of suicides through 2015 have been ages 15-17, the number of 10-14-year-olds killing themselves is on the rise, according to the Georgia Bureau of Investigation’s Child Fatality Review Unit (GCFR).

To date, 18 children have taken their own lives in 2017.

Many of the suicides were carried out with guns, per the GBI’s data, with hangings as the second most popular method.

Bermudez knows.

She moved her son to Atlanta from St. Croix.

From the beginning, she said, he was bullied relentlessly in school. She read his journal following his death. He had documented page after page of torture. And each entry was worse and worse.

It had changed him.

“He wasn't the same active little boy who used to play and run and play with the sisters. He wasn't the same,” his mom remembered.

At first, he told her about the bullying at school, but eventually he grew silent.

“[I would] go to the school and they wouldn't do anything about it,” she said.

But on April 16, no one would be able to do anything about it ever again.

She remembers that day vividly.

“[I] went upstairs and I unlocked the door. Usually, [when] you open the door, you see the entrance to the closet. That day, I saw the whole closet—no doorway or nothing. Like it didn't have no walls. I just saw my son hanging there.”

“That's an image that's on mind forever.”

Trebor Randall, GBI special agent, wants families to talk about suicide in their homes with their kids.

“We cannot sugarcoat this subject. As sensitive as it is, as tragic as it is for a parent to lose a child, they don't want this to happen to another family,” she said.

Last month, Georgia had six children, under the age of 18, commit suicide.

“That was cause for concern,” Randall said. “Anytime one child takes their own life because they feel like they have no other option, that's alarming for us.”

The GBI recently took over the Georgia Child Fatality Review Unit and hopes to bring awareness to parents, children and schools.

“We're trying to be more proactive,” she said. “Suicide is at the top of our list as well because, we feel like in most cases if there is intervention early enough we may be able to save these kids.”

She hopes to equip parents, teachers and peers of the students on how to better deal with the crisis; how to better deal with stress; how to better deal with their peer-to-peer interactions; so that they better understand and know the warning signs.

“Just like, they talk about a village is needed to raise a child, it takes a village to save a child,” she said. “It’s important to listen to your kids, turn off the TV.”

If parents can teach their children coping skills; teach them that it’s not the end of the world, Randall said, maybe they can also talk to them about their emotions. And listen with empathy. Even if it’s uncomfortable or feels like a sensitive topic, he said, talking is key.

“It’s never too sensitive to share with other parents and other individuals who care about the welfare and wellbeing of children,” he said.

It's what the GBI likes to call, "saving Georgia's children."

“You know, if we could save one, but we don't want to stop there,” Randall said. “We want to saturate the state with this message.”

Psychiatrist Dr. Michael Rosen said that Bermudez’s son isn’t alone. Far from it. In fact, he said there is a mental health crisis in Georgia. And it continues to affect younger and younger children.

“There is no question that, just anecdotally speaking, we are seeing a rise in the number of cases of people that are having thoughts of suicide or attempting suicide,” Rosen said, especially with high-achieving kids.

“The kids are pushing and pushing… taking the hardest possible curriculum they can possibly take and then they're involved into sports and extracurricular activity they're not getting to bed until 12:30, 1 in the morning, they're getting back up at 5:30, 6 in the morning.”

They are getting four or five hours of sleep at best. They should be resting for nine, Rosen said.

“They’re like a hamster on a wheel, and they feel like there's no end in sight, so they are chugging and chugging and pressing to get to college and when they get to college and press to make the best grade, to get to the next level.”

But, he said, there is no end in sight for these kids and that's what happening.

“They're starting to feel helpless, they are starting to feel hopeless and that's what leads to suicide—they don’t have life experience to deal with it.”

And there’s no help for them in Georgia, he said. Not enough hospitals. And he called mental health care in the state “horrendous.”

“There's absolutely not enough help. This is the crisis that we're in in Georgia. [We] lack access to good care,” he said. “But nobody is paying attention. Mental health is the poor, step-child… it's worse than Cinderella, in Georgia and in the country. We have a crisis.”

According to the GCFR, in 2015, there were 35 youth suicides--16 of those were between 5-14 years old. This year, 10 children have killed themselves with guns, six have hanged themselves and two have overdosed. Ten of those suicides were white males.

Schools, he said, are not doing their jobs to address bullying issues, nor are they paying attention to what's going on because he is starting to see younger and younger kids who are being bullied, and who are having suicidal thoughts.

“Yesterday, I had a 10-year-old who was in here saying that about three or four years you tried to hang himself,” he said. “There's hope but we have to do a better job.”

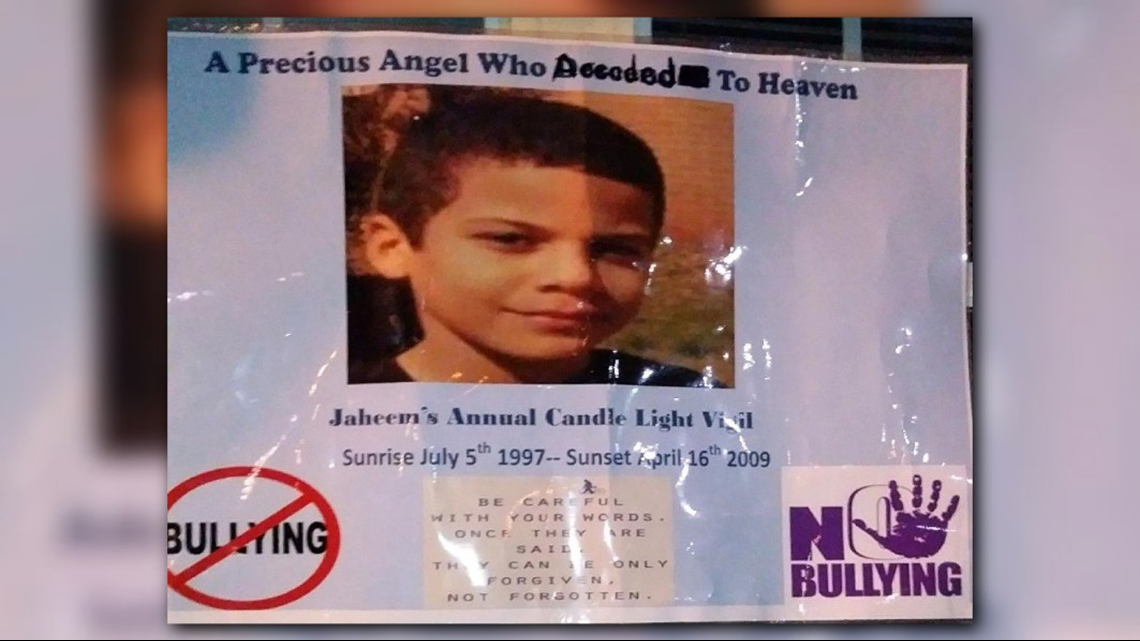

Now, Bermudez holds an annual candlelight vigil every year. It’s something that she said helped her get through her own grief and she hopes that it helps others dealing with the same pain.

“I've learned how to cope with it,” she said about losing her son who would have turned 20 this July. “At first it was a real, like, that was my only son.”

“I just asked God to one day give me some closure, but I don't know if that's going to happen,” Bermudez said, who said that her advocacy for so if I prevention led to an anti-bullying act getting passed in the Georgia legislature.

She said that she wants kids to know that they need to keep the topic out there and the discussion loud.

Don’t stay silent, she urged.

“Not under the rug. That's what they tried to do with my son, sweep it under the rug and move on,” she said. “Speak out; speak out. Don't keep it in.”

And to parents, she urged them to ask your child questions.

“How is school?”

“How is everybody treating you?”

“Is everything going all right?”

And while she fights and speaks out on the topic for other parents and children, so that no more are lost to suicide, she still wonders what might have been with her own son.

“Oh my God, he was so handsome. I don't know. I don't know. But I just wish you was here.”

After 14 children committed suicide in the past two months, the GCFR partnered with Georgia Department of Education and the Georgia Department of Public Health, and together conducted a series of Suicide Prevention Summits for school personnel.

The sessions took place in Macon, Rome, Gainesville and in Gwinnett County—each had had suicides of children under 18 years old reported for three years in a row. More than 200 teachers and school employees were trained in suicide prevention, given child death data including youth suicide stats, and given resources and tops on how to deal with a suicide in their schools.

More programs are planned for September throughout the state.

If you think that someone could be suicidal, call the U.S. National Suicide Prevention Hotline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).