Teen finds team to score touchdown in life: How new DFCS program could prevent child abandonment

Trey bounced around from family to foster care and even a group home. Now, one program has turned his life around. Here's why it's not widely available.

The joys of football include the rush of the run and the roar of the crowd when a touchdown is made. While we all celebrate the one holding the ball, it takes a team to walk away with the win. So it is, in the game of life.

Trey Smith knows what it’s like to have a team setting up the supporting plays to help achieve the victory. Of course, for Trey, football is simply a metaphor, a way to think about therapeutic foster care (TFC).

“It was a whole different, total ballgame,” Trey’s foster mom, Annmarie Small said.

Trey came into the custody of Georgia’s Division of Family and Children Services (DFCS) when he was five.

“My teacher called DFCS and told them that my arm was burnt,” Trey recalled.

Since then, he’s lived with relatives, a foster family, and in a group home. Between the abuse, bouncing around and a mild intellectual disability, Trey didn’t just need housing and love, he needed behavioral therapy.

To get it, DFCS connected with Creative Community Services. CCS starts with a pretty basic question that all too often gets lost: What does this child need?

“Everyone’s coming to the home, at least four or five workers come in and we sit around the table and we talk. Trey talks,” Small explained.

HOW TFC WORKS

Those in therapeutic foster care are generally teenagers with complicated diagnosis.

“They may have autism and behavior issues. They may have developmental disabilities. And also have mental health issues,” the founder of CCS, Sally Buchanan said.

Training is also given to both the foster and biological parents, if the plan is for the child to go back home.

“You can’t just say, here’s your kiddo back, now I need you… you should be able to get your act together and you should be able to take care of this child. That’s not going to happen,” Buchanan explained, adding that parents also need new tools or the cycle is "doomed to repeat."

In the past five years, half of the children abandoned to the state’s child welfare system were placed more than once. An abandoned 10-year-old diagnosed with bipolar moved around three more times because either the caregiver couldn’t cope or her behaviors were too much to manage.

Small said the support team provided through TFC is critical.

“I don’t think this program could survive without that," Small said.

RELATED: Broken furniture, broken hopes: Georgia mom stuck in loop trying to get help for son with autism

Small and her husband have been foster parents for about 20 years, starting with younger children in New Jersey. They transitioned to TFC when they moved to Georgia in 2017. She agreed, the needs of the children in TFC are greater and the behavioral challenges more severe. But she’s watched how it’s made a difference.

CHILDREN IN HOTELS

Creative Community Services is limited. The program can only handle about 77 teenagers in state custody each year.

“We probably get four referrals a week of kids that they are living in hotels and it’s because no one can serve them. But we don’t have the resources to serve them,” Buchanan said.

She is talking about the state’s practice of putting children in hotels until they can find them a bed in a more appropriate setting, usually a Psychiatric Residential Treatment Facility, or PRTF. While being in a hotel, the children are supervised 24/7.

In 2019 – DFCS paid to house more than 600 children in hotels – most of them teenagers with intellectual disabilities and significant behavioral concerns. The cost? Roughly $1,400 a day. That’s nearly four times as expensive as a treatment facility and five times more expensive that TFC.

“Money doesn’t solve things. What solves things is the right amount of money plus the right service at the right time,” former DFCS Division Director Tom Rawlings said.

A NATIONAL PROBLEM

Georgia isn’t alone. According to a national study by Beth Stroul at the University of Maryland, two thirds of states have written a law or regulation to "prohibit" children from being abandoned for mental health services.

In Stroul’s report, ‘Relinquishing Custody for Mental Health Services: Progress and Challenges,’ she notes 78-percent of states have some type of diversion strategy.

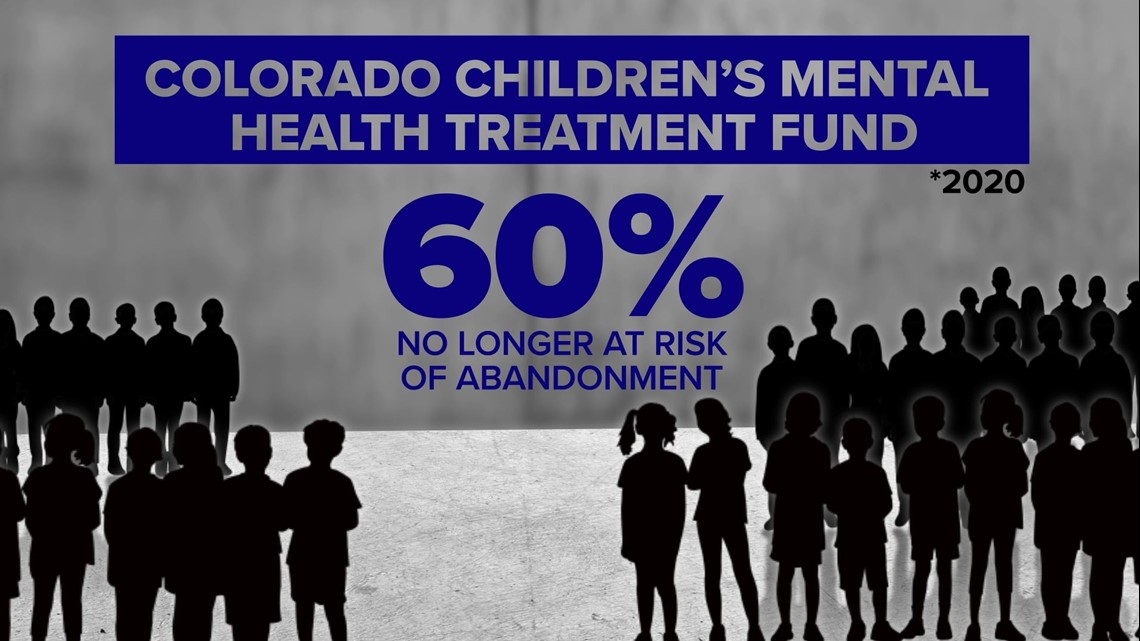

11Alive's investigative team, The Reveal, talked to Colorado about its program. Lawmakers in that state created a fund to help under and uninsured children access mental health services.

“Families lacked the ability to pay out of pocket for these needed services and the result was they were turning to child welfare,” said Stacy Davis, the program manager for the Children and Youth Mental Health Treatment Act.

In 2020, the program’s annual report said caseworkers helped 185 children find and pay for mental health services. Of those discharged, 60% were no longer at imminent risk of being abandoned.

“The number is small but the impact I hope is huge,” Davis said.

Georgia said it already has a way to help these children, paying for the under and uninsured as a last resort. But families said getting connected to those services is cumbersome and too often leads to yet more denials.

Other states are using voluntary placements, basically access to intensive mental and behavioral health services, without parents giving up custody. That’s what Rawlings hopes DFCS will do with TFC, despite his absence.

“The more we can get the provider to go out and see the family in their environment, treat not only the child's issues, but also help the family deal with the child's issues, that's really where our long term goals should be,” Rawlings said.

GEORGIA ROAD BLOCKS

Georgia lawmakers approved $6.7 million in funding this year to expand TFC. Children in state custody and those at risk of being abandoned, who can show such a program is “medically necessary," would be included.

According to Stroul, 52% of states report using some type of voluntary placement agreement to prevent abandonment.

According to a spokesperson with DFCS, the money currently allocated can serve about 500 youth. The division hopes to grow the program in the next few years to double that number.

Before it can serve that many children and youth, it needs to find enough foster families, therapists, care coordination workers and behavior aides who have proven they can meet the standards of the states’ TFC program.

While expansion of TFC is seen by most as a positive step, it's still an extreme option and raises the question, why?

Why does a child have to leave their home to get good case management and care?

“If you have a cut, you may go to the urgent care or you just may need a Band-Aid. We have been working to build and still have a lot of work to do to build a mental health system that has that range of options the way we do for physical health,” Rawlings said.

Trey will never go back to live with his mom, but he is learning how to live independently. He has a job at McDonald's.

“I clean the lobby and take out trash. Sometimes I be on fry product making nuggets,” Trey said.

He’s learning how to manage money, coordinate his clothes and keep a house clean. He’s also learning to manage his anger and better communicate his feelings.

Trey has experienced traditional foster care and TFC. When asked what’s different he responds, “I get the help that I needed,” adding his recent successes likely wouldn’t have happened if it weren’t for the program.

His team has taught him how to catch the ball, now he’s ready for his touchdown.

POSSIBLE SOLUTIONS

As part of a data fellowship with USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism, The Reveal, is showing how the challenges of raising children with severe emotional and developmental disabilities can lead to abandonment.

During this investigative series, we are asking those in the middle of it, "what is a solution." Here's what they say.

- Create voluntary placement options that allow parents to access state-funded services, while retaining custody and input in treatment.

- Allow in-home parent skills training to address behavioral issues.

- Get involved! Become a skilled therapeutic foster parent or provide short term respite to those who are.

The Reveal is an investigative show exposing inequality, injustice, and ineptitude created by people in power throughout Georgia and across the country.

This story was told as part of a 2020 Data Fellowship with the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism.