ATLANTA — Atlanta is often described as a "Tale of Two Cities."

It has the highest income inequality in the country, with a massive racial wealth gap between Black and white families.

As a cultural epicenter, Atlanta is often viewed as a hub for entrepreneurship, innovation and creative endeavors. Despite the city's growth, there are still invisible barriers present that serve as subtle reminders of the past.

Historically, roadways and their names were used as invisible walls to segregate communities and slow integration in concerted effort to create two Atlantas. Segregation using roadways as a tool has a more than century-long history in the city.

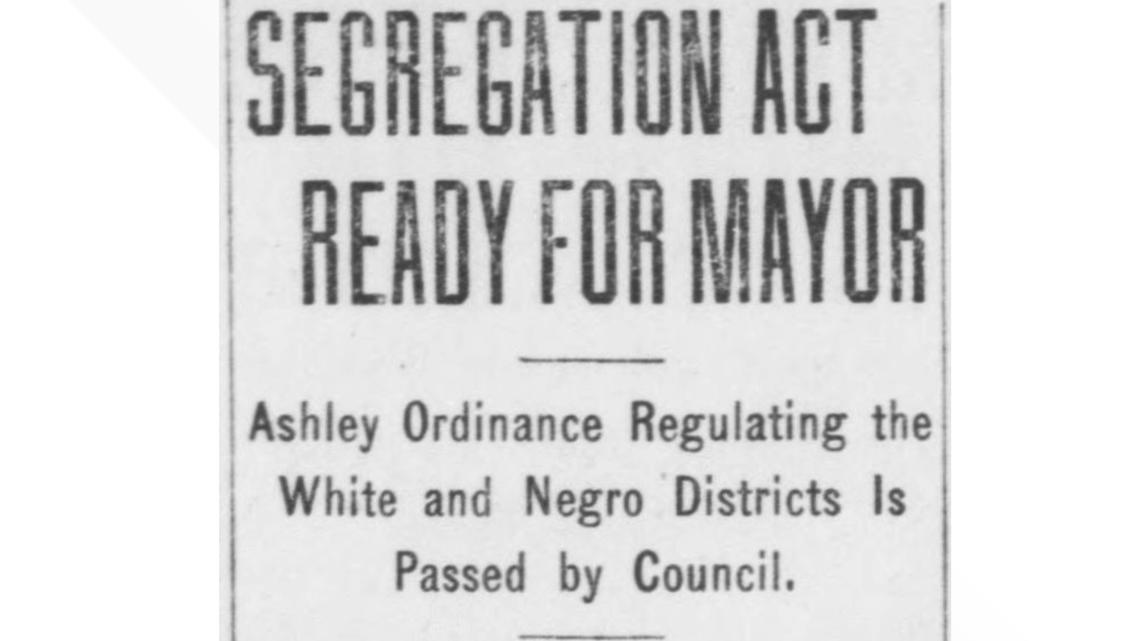

The Ashley Ordinance of 1913, named for 4th Ward City Councilman Claude L. Ashley, was a racial zoning ordinance that tried to legally restrict where Black people could live in Atlanta. The Georgia Supreme Court would rule it unconstitutional nearly two years later, but the effects of the ordinance had already taken root.

Another well-known example was a wooden roadblock built on Peyton Road, referred to as Atlanta’s Berlin Wall, which stood from December 1962 until March 1963. Mayor Ivan Allen, Jr. ordered the barricade, which severed the main thoroughfare connecting the Black and white sections of the Cascade Heights neighborhood. The wall was meant to prevent Black residents from moving into what was considered the "white side." A judge ruled it unconstitutional, and then-Mayor Allen would order its tear-down.

The most recognizable and effective barrier, according to historians, is Interstate 20. It has served as the largest historical barrier between Black and white neighborhoods as north of I-20 were white neighborhoods and south of I-20, Black communities.

Ponce De Leon Avenue: A dividing line

Sometimes, the streets even change names to enforce separation. One example falls along the dividing lines of Ponce De Leon Avenue, a 16-mile road that cuts through the city.

When cross streets intersect with Ponce De Leon, they change names. Boulevard becomes Monroe Drive, Moreland Avenue becomes Briarcliff Road and demographics change.

Historians say this was a strategy so people of different races didn’t have to share the same address.

"White America did not want to be seen as living on the same street as Black Americans, and it feeds into the American capitalist idea of property value," Dr. Maurice Hobson, historian and Georgia State University professor, said. "So, of course, you know, white property value [is] higher than that of Black Americans."

Pamela has lived along Ponce De Leon Avenue for about eight years and sees the division.

"Even MARTA separates the north from the south and the east and the west," she said, as she was waited for her bus.

Two neighborhoods, one to the north of Ponce and one to the south, illustrate this issue.

North of Ponce is Virginia Highland – where almost 80% of residents are white, and the median household income is around $112,000.

South of Ponce is Old Fourth Ward – which is now experiencing a huge demographic shift. Back in 2000, the neighborhood was 76% Black, with a median household income of less than $20,000. The latest numbers show that the neighborhood is 38% Black, and the median household income is $68,000.

Rapid gentrification has blurred the lines.

Data shows that, as property value and household income increased in what once were financially struggling areas south of Ponce, the population of Black residents began to decrease.

The median household income for Atlanta as a whole is $77,655, with a 40.8% white and 47.6% Black population.

While times have changed, some of the issues, like affordability and housing, still remain.

"They just got rid of some of the housing projects," Nesha, a resident of the area, said, referring to the Village of Bedford Pines. The subsidized housing was originally along Boulevard, south of Ponce.

In an ever-changing Atlanta, Hobson says how the city moves forward will depend on how it will be led.

"People should be put over policies," he said. "People should be put over profits. People should be put over politics."